On-post officers' clubs were particular targets of black protests against segregation. An Army regulation issued in December 1940, Army Regulation 210-10, stated that

no officers clubs, messes, or similar organization of officers will be permitted by the post commander to occupy any part of any public building ... unless such club, mess or other organization extends to all officers on the post the right to full membership.1

Black officers challenged segregation at Camp Stewart, Georgia, for example, by requesting admission to the officers' club and being refused. Other officers would gain admission to local officers' club, sit down at table, and wait to be told to leave.2

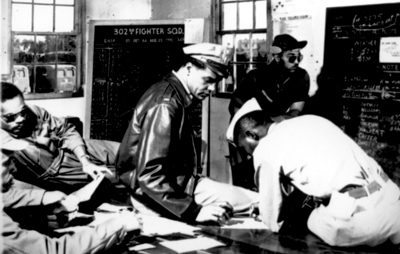

Black pilots were involved in some of the most disciplined and organized protests undertaken during the war. Selfridge Field near Detroit was a training base for two units of the 332nd Fighter Group, the 477th and the 553rd, and Selfridge Field was segregated. Some of the black airmen at Selfridge who had been trained at Tuskegee attempted to desegregate the officers' club, post theater, mess hall, post exchange, and other facilities. At the post theater, for example, where blacks and whites were separated by a white line down the middle of the theater, black airmen would wait until the theater had darkened and then jump to seats on the "white" side and remain there for the rest of the movie.3

Pilots at Selfridge Field

Source: National Archives, Item 208-VM-1-5-68A

In 1943, the general commanding the unit had declared that the officers' club at Selfridge was for whites only and that black airmen would have to wait for a second club to be built; black officers responded by entering the existing club and were arrested. Other black officers applied to the white officers' club and were denied membership. In early 1944, officers planned a new approach for desegregating the officers' club: sending small groups, to prevent any accusation that they were encouraging a mutiny, to attempt to desegregate the club. They were turned away and threatened with court-martial. Over the course of the next five days, small groups attempted to integrate the officers' club. The post commander then closed the club. Within weeks, the black officers had a small measure of victory: the Army inspector general sent a team to investigate conditions on the base and both the colonel and lieutenant colonel commanding the group were relieved.4

By this time, race relations at Selfridge were so bad that the Army Air Forces decided to move 477th and 553rd to other locations. The military's primary concerns were an ongoing dispute over the use of the officers' club and concern that the Selfridge troops would be influenced by the ongoing racial disturbances by civilians in Detroit.5

James Warren at Godman Field

Source: James Warren