Non-violent protests by blacks in the military contributed to changes in military policies with respect to segregation. Even if the military might have preferred not to become involved in the "social policy" issues relating to discriminatory practices, non-violent protest put pressure on military leaders to act, because protest was a disciplinary problem that might interfere with the successful prosecution of the War. Over time, the military would come to realize that discrimination was "fatal" to military efficiency, and the military leadership acted, both in the United States and in the theaters of war, to address some of the problems.1

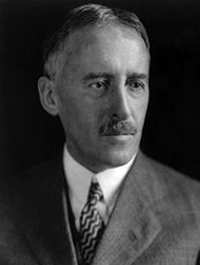

Secretary McCloy

Source: Corbis

The military recognized that segregation was one of the major sources of dissatisfaction for black members of the military. In 1943, a War Department report noted that among the problems noted on visits by observers to posts and bases, segregation was a recurring theme. The report specifically noted dissatisfaction over segregation in the mess halls and post theaters and on military and civilian transportation. As racial problems mounted, the War Department appointed Assistant Secretary John J. McCloy to chair the Advisory Committee on Negro Troop Policies, later referred to as the McCloy Committee. The committee recommended that the General of the Army, General George C. Marshall, issue direction to the commanders outlining their responsibilities to resolve problems involving inequitable treatment. Marshall subsequently issued instructions to the commanding generals of the Army Air Forces, Army Ground Forces, and Army Service Forces.2

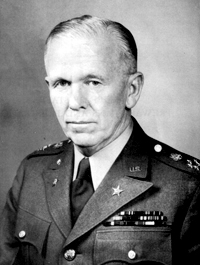

General George Marshall

Source: US Army

Marshall also called for efforts by commanders to address issues raised by black soldiers. In July of 1943, Adjutant General James A. Ulio issued orders on behalf of Marshall requiring that every soldier have equal access to recreational facilities. Field commanders and Army inspectors still reported confusion about the policy. As a result, the Army issued new direction that prohibited segregation by race, although not segregation by unit, which would lead to the problems at Freeman Field. The new direction applied to post exchanges, military transportation, and on-post. Some of the efforts of the military leadership were at least partially successful; when the Adjutant General issued another order in mid-1943 that military buses provide equal access for blacks and whites, the incidents of disturbances related to bus segregation decreased.3

Secretary of War Stimson

Source: State Department