Mark Edwin Peterson

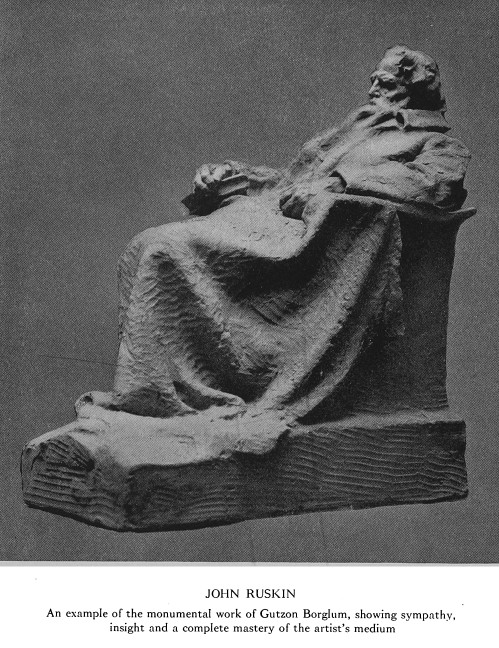

Undergraduates at the University of Virginia eventually come across Clemons Library on grounds, with its media center and learning commons, just paces away from the main research library. Outside the main entrance to Clemons stands a bronze figure rooted to a granite foundation but getting ready to soar on fashioned wings. This dramatic monument remembers a student, James Rogers McConnell, who died as a volunteer pilot for France during the early years of the First World War, before America had joined the conflict. The statue, created by the famous Gutzon Borglum in 1919, signified a great deal to the alumni and administrators who commissioned it, and it continues to have meaning for the university today.

This paper examines McConnell’s actions that made him an important alumnus, the history of the decision to build a monument to him, and the situation in Charlottesville at the time that made the death of the pilot worthy of such a statue. Along the way, the paper argues that American concerns about the war made people eager to see the brave airman as a model for young college students, and that interest in supporting France meant that many saw encouraging volunteers for war as a positive form of propaganda. On the ground in Charlottesville, however, other concerns about the role of the university in Virginia and the nation meant that the statue became part of another level of messaging to tell the people of the town that young UVA students like McConnell had done great things and would continue to do more, helping to shape America. In some ways, this promise of success came with the understanding that others, unlike McConnell, would not have the chance to share in the status and opportunities offered to the elites studying at the University of Virginia.

This paper examines McConnell’s actions that made him an important alumnus, the history of the decision to build a monument to him, and the situation in Charlottesville at the time that made the death of the pilot worthy of such a statue. Along the way, the paper argues that American concerns about the war made people eager to see the brave airman as a model for young college students, and that interest in supporting France meant that many saw encouraging volunteers for war as a positive form of propaganda. On the ground in Charlottesville, however, other concerns about the role of the university in Virginia and the nation meant that the statue became part of another level of messaging to tell the people of the town that young UVA students like McConnell had done great things and would continue to do more, helping to shape America. In some ways, this promise of success came with the understanding that others, unlike McConnell, would not have the chance to share in the status and opportunities offered to the elites studying at the University of Virginia.

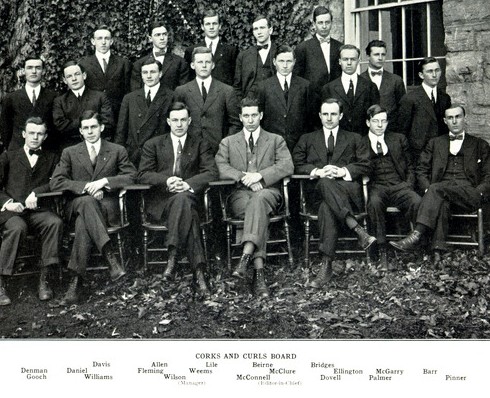

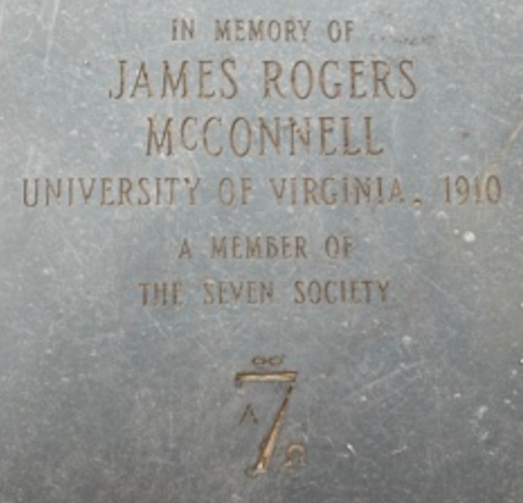

James Rogers Mcconnell had been born in Chicago and considered himself a New Yorker, but he spent the last years of his childhood in Carthage, NC. His wealthy parents sent him off to college at one of the most respected universities in the South at the beginning of the twentieth century, the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Jim, as he was known, started a whirlwind social life at school in 1907, becoming a member of the German Club and the New York Club, working as an assistant cheer leader and editor-in-chief of the campus yearbook, while joining several fraternities, as well as secret societies such as the Hot Foot Society, O. W. L. and T. I. L. K. A. He appears to have joined the mysterious Seven, as one of the early members, and was the founding member of the Aero Club branch on campus.1 Before finishing his degree, McConnell returned to Carthage some time during the spring of his third year to work as a land agent for the local railroad.

He had traveled often to France as a boy on many enjoyable trips with his family, so McConnell felt called to help when the Great War started in 1914. By the beginning of the next year, he had organized a job for himself driving an ambulance on the Western Front.2 He worked along the line for almost a year, seeing the worst of battle in the trenches, while receiving a commendation and writing a well-received article for Outlook magazine about the war. It did not feel like enough. “All along I had been convinced that the United States ought to aid in the struggle against Germany. With that conviction, it was plainly up to me to do more than drive an ambulance.”3 So, he joined the French Foreign Legion, which allowed a neutral American such as him to swear allegiance to the legion and not to France. McConnell quickly joined their new Air Service branch to start training to be a pilot. By April of 1916, he joined six other Americans in a new squadron just for men from the United States that eventually came to be known as the Lafayette Escadrille.4

Of course, the United States still remained out of World War I at this point, but leaders made it clear that they opposed Germany and saw German belligerence as the main cause for the conflict. The American expat community in Paris was especially supportive of France at this time and found the greatest hope in the idea that the United States would eventually join the fight against the Germans. A prominent surgeon, Dr. Edmund Gros, who had set up the American Hospital and then the American Ambulance Service, decided to establish the Lafayette Escadrille to give the Americans a specific role in the rapidly developing air war. With the help of many of his rich patients, including the Vanderbilts, Gros pushed French authorities to allow an American squadron under French command and then raised money to supplement the pilots’ poor pay.5 A committee of wealthy expats organized equipment, housing, and combat rewards for the Americans, so that the squadron could begin formal training and then combat missions by the middle of 1916. The Lafayette Escadrille always had the role, from the very beginning, of advertising American support for the French war effort to the point of supplying men to fight. By the time McConnell and the others flew serious missions over the Battle of Verdun, the Americans numbered fifteen and it would continue to grow steadily.6 224 Americans joined the escadrille by the time the United States sent troops to Europe.7

For his part, McConnell always knew that representing America as an active combat pilot remained an important part of serving the interests of France. His plane sported the symbol of UVA’s Hot Foot Society, and he wrote more articles about his experiences in popular magazines, which were eventually collected into a book.8 After a few months of flying, McConnell seriously injured his back after a bad landing in August. He only flew one more mission before the end of the year, spending much of his time crafting articles and urging the U.S. government to support France.9 His injuries continued to plague him into the next year, affecting his ability to scan the sky for enemy aircraft, which could make for difficult flying even as the Germans were retreating to the Hindenburg Line. “They used ground machine guns on us, however, for the first time in my experience. I could see the stream of luminous bullets going by me like water falling in the sunlight.”10 On March 19, 1917, his plane got separated from the two others on patrol over the Somme, and McConnell was shot down. His body was stripped of everything and left in the apple orchard where he crashed until discovered by French troops three days later. McConnell was the fourth of the initial American pilots to be killed and the last before America entered the war in April.11 Earlier, he had written, “Next to falling in flames a drop in a wrecked machine is the worst death an aviator can meet. I know of no sound more horrible than that made by an airplane crashing to earth.”12 However, McConnell had also said of another pilot that he did, “not think Prince minded going. He wanted to do his part before being killed, and he had more than done it.”13 In a letter left for his comrades, McConnell told them to only hold a ceremony if they felt the need for themselves.14

The University of Virginia community reacted swiftly to news of the pilot’s death. At the faculty meeting, roughly a week later, a resolution was passed to bring McConnell’s body back to campus even though French law forbid the repatriation of casualties in the midst of fighting, and the family had not yet been asked. At that meeting, the faculty also approved the erection of a suitable monument in some appropriate spot on university grounds in honor of the dead alumnus. Expressions of sorrow came from all around, including from the secret societies he he had been a member of, as did pledges of support for a monument.15 McConnell was the first UVA student killed in the war. A piece in the school yearbook from the next spring described him dying for France, for America, for civilization. “He was a brave man, an idealist, who understood the profound significance of this war and who had a passionate and poetic love for the people in whose service he gave his all. His example, his character, his high vision, inspire all Virginia men who follow where he led across the blood-stained fields of battle.”16 That article noted that of almost ten thousand alumni for which there was any kind of record available, over two thousand had enlisted in some type of war service, fifty-three of them as aviators.17 In a letter to McConnell’s father, the president of the university, Edwin A. Alderman, wrote on March 28, “He has written his name high upon the rolls of those who have illustrated by valor and courage the spirit of this University and the loftier qualities of American citizenship.” Alderman also mentioned that he thought there should be a “some beautiful and noble memorial” placed on grounds.18

Certainly others felt similar sentiments about McConnell’s death. His most recent home town, Carthage, held a service less than two weeks after his death, contrary to McConnell’s wishes in some ways, dedicating a memorial in front of the courthouse that would come to include two plaques and an obelisk in the style of the Washington Monument. A similar service was held in Paris the next day.19 France eventually sent their own plaque to the University of Virginia, “the institution where his moral character was duly tempered,” as wrote Ambassador Jusserand,20 and also established an elaborate memorial at the site of his crash. The Seven Society sent a wreath of their own to the UVA services and then a plaque, as well. Eventually, a huge monument for the Lafayette Escadrille as a whole would be set up just north of Paris, which is where McConnell was actually buried, along with the forty-eight of the sixty-eight American escadrille members killed in combat.21

In Charlottesville, however, the focus remained all along on what the pilot had meant for the students and faculty at the university. After initial enthusiasm for a memorial on grounds, the suggestion for a similar commemoration also came from McConnell’s brother-in-law, Mitchell D. Follansbee, a prominent attorney and professor in Chicago. Alderman replied that it should be more than just a plaque, but something created by a real artist such as Saint-Gaudens, Borglum, or Taft. Students took it upon themselves to approach Gutzon Borglum and make him an offer. And so, a formal commission was agreed upon by that summer. Alderman remained deeply involved in the design of the statue all along, even promoting Borglum to McConnell’s mother and suggesting ideas to the artist for how the sculpture should look, something dignified in uniform. Eventually, Borglum would come to the main campus to pick a site just off the Lawn that would be near where the eventual Alderman Library would be built years later.22

The sculptor had already done some sculpture for the university in the rebuilding of the portico of the famous rotunda. His final design for “The Aviator,” his tribute to McConnell, imagined the airman as Icarus, flying free from his prison with wings of wax. The figure itself is a Beaux Arts interpretation of Classical themes, like much of Borglum’s earlier work, but it is also an unusual piece for him in its dramatic flair of outstretched wings and the struggle for height. A modest codpiece is the only reference to modern tastes, but this too has an individual style that separates the sculpture from other work of the time and from traditional funeral sculpture. Borglum, himself an early member of the national Aero Club,23 had written a decade earlier, “But you must speak your soul’s cry and if your heart is right, it will be our nation’s cry and we will all understand.”24 He thought that artists should not only give up on imitating European style but also live full, dramatic lives that would come through in their work. “The Aviator” clearly seeks to express that. The bottom portion of the monument has much more concrete references to McConnell and modern life, with biplanes carved into the foundation stone and a hemisphere of bronze showing storm-tossed waves and a dramatic Borglum signature. It would take a deeper analysis to discuss the meaning of the prison from which the figure is trying to escape, but it is easy to imagine the ambitious pilot getting too close to the sun in his love of flight, only for his young dreams to be smashed. Later works by Borglum would have more commentary about modernity, but shortly after finishing the “The Aviator” he turned most of his attention for the rest of his career to gigantic monuments that expressed their American spirit in size: the Confederate monument of Stone Mountain in Georgia and Mount Rushmore.

For Alderman and many at UVA, the American spirit was the Virginia spirit. “The chiefest contribution of Virginia to American life has been men, great governmental ideas, and a great spirit.”25 Alderman thought of Virginia as the mother of all that was good about America through Washington, Madison, and Jefferson. For the modern age, the country should look to the Commonwealth for leadership and example. Even General Lee provided a model, in Alderman’s telling, in that Lee took up the cause of the state and when that grim work was done, he set about the work of reconciliation with the same determination.26 McConnell was seen as also bravely doing what was necessary for the future of the country. Others said that it was Virginians of this generation, perhaps including Woodrow Wilson, who would keep the country intact. More specifically, the men of the University of Virginia, from the old colonial stock that was the essence of what was truly American, as they wrote in the yearbook, would lead America through difficult times, inspiring the country like McConnell had.27

The statue was unveiled on June 10th, 1919, the third day of commencement, presented by Rev. Robert Wilson of Princeton, who had been McConnell’s college roommate, for the alumni and received for the university by one of his law professors who had taken leave to serve in France, Armistead Dobie.28 In his commencement speech that day, Alderman said, “You leave here at a supreme hour when the youth of your nation has passed into maturity, when its isolation has become leadership and when its idealism, spiritual as well as material, is linked up with the fate of the world.”29 Dobie, for his part, said of McConnell, “As dangerous and as useful as his duties were as an ambulance driver, these non-combatant tasks did not seem to him to fill the measures of his loyalty or even appear approximately to transcend the limits of his love for France.” He described the new frontier that lured McConnell to risk his life, air combat. Part of the appeal of flying for McConnell rested in the fact that it provided a chance to soar above the world of others. “For him, victory or defeat is spelled in terms of individual achievements.”30 As an example for the university, McConnell symbolized self-sacrifice and dedication in service of the nation, but he also showed them a path in this direction that led through individual courage and ability, very different from the squalor and destruction in the trenches that many volunteers faced in modern war.

Of course, students today who see this dramatic monument in front of the undergraduate library can be forgiven for thinking this is all a bit much for a big man on campus who never bothered with graduating and for whom there does not appear to be any official record that he killed any enemy in combat. In terms of French lives saved, McConnell’s ambulance driving seems a much greater help than the entire squad of American pilots and the expensive training they received. However, Ross F. Collins notes that the myths of war make it acceptable and, when wrapped in traditional narratives of the hero, can work as propaganda to build support for war. “War creates mythic narratives.”31 After all, America did finally join the war in Europe, though German u-boots had a lot more to do with that.

For UVA, the Great War, already in progress, offered a challenge and a promise that the university could be an important part of the national story, one that reflected back well on the student body as a whole. Monuments of crisis like this war encouraged young men to rise to the occasion and become knights of the air, heroes of legend, even as reports came in about the true nature of the conflict.32 Part of the enthusiasm for the Lafayette Escadrille, and the monuments dedicated to it, came from an acknowledged understanding that these Americans not only strengthened allegiances with France but also communicated to the United States the nobility of engaging in combat. But there was also the appeal of McConnell himself for the people at UVA that helped to bring about this statue. Rich, popular, and talented, McConnell used his connections to make a mark on the world just as he had at the university. Older alumni and faculty, just the sort of people erecting so many monuments between the two world wars, could imagine that they had been like the daring pilot in their youth, and that their donations and teaching worked to create more like him. Much of this is fantasy, of course, but as Corey Van Landingham reminds us, “The present is always revising the past.”33 Community leaders wanted the war to be heroic, and their work to be heroic. The statue makes it so, at least in memory.

“The Aviator” also, perhaps consciously, ties the university in with the city and even the entire state. Paul Goodloe McIntire, an alumnus and donor to Charlottesville, had commissioned a stature of Robert E. Lee to stand in a new city park, which he also donated.34 The General Lee statue, dedicated in 1924, would take the longest to finish, but it was part of a series of four statues that McIntire installed, starting in 1919, the same year Borglum completed the McConnell statue. Along with the Civil War generals, Lee and Stonewall Jackson, Lewis and Clark, as well as George Rogers Clark, the “Conqueror of the Old Northwest,” were immortalized. President Alderman spoke at all four dedications for the city and involved the students in these events as much as he could. All five men had connections to the region, but the story that the statues told centered on the importance of these individuals to national history, and particularly Virginia’s role in it. It is probably that Alderman involved himself in the design of these statues just as much as he had worked with Borglum. Certainly the program of the figures fits in with Alderman’s view that history had tied Virginia and the nation together.

Louis P. Nelson writes that in thinking about these four images in bronze it is important to understand how they fit into the layout of the Charlottesville.35 George Rogers Clark, with his kneeling, subjugate Native Americans, for example, sits on the easternmost property of the university, near the popular restaurants of a neighborhood known as the Corner. Looking up Main Street, the figure of Clark, and its message of American Empire, ties UVA to the city’s downtown where the other statues were built on or near sites of demolished African American neighborhoods.36 If the earliest historical figure has links to the university, then the McConnell monument works to illustrate how the education of the students taking place on grounds connects with, and soars above, that Virginia history symbolized by all of the Charlottesville statues constructed in this period. “The erection of the Lee monument was the culminating act in the remaking of a city as the new Old South, with all the attendant political, racial, educational, and cultural implications,” says Nelson.37

Whether “The Aviator” tied into the deeply-held program of white supremacy that was part of this view of the South is less clear. Much has been written about the Lee statue and its distance from current academic views of the general’s meaning for history, especially in light of the deadly Unite the Right Rally that took place in Charlottesville in 2017. Statues can mean a lot more than history books. Certainly they can carry a great variety of different meanings from what is any monograph.38 In this case, the McIntyre statues clearly told viewers that this history of triumph and resilience did not include the Black community of Charlottesville in the builders’ eyes. Many people, in fact, could be expected to understand from these statues also signified the racism that helped build this vision of Virginia. However, the only point that can be addressed here, briefly, in terms of “The Aviator,” is the issue of whether the public message of the McConnell memorial connects the academic vision of Alderman for the university to the racial oppression in the city at the time.

Though they did not always consider themselves hostile to Blacks, UVA students at the time often shared in a casual sense of white supremacy,39 Though it could be openly hostile as well. In 1922, while the Lee statue was being finished, the school yearbook included, without apology, an illustration of Klan riders on the front page of its club section.40 Faculty at UVA promoted the Lost Cause mythology that had such a large role in the twentieth-century spread of Confederate monuments. In fact, Alderman wrote that Heath Dabney, a leading proponent of the Lost Cause, worshiped the McConnell statue and brought students to see it.41 The strongest connection to white supremacy, though, is visible in the figure itself, in that it characterizes an ideal of whiteness that highlights a sense of difference from anyone else. Like the young figures of Faith and Valor at the base of the Stonewall Jackson statue, the airman has the look of an Aryan “type” that would be recognized in the Kultur magazines of the German Empire and the medical lectures on the grounds of UVA itself at the time.42 Only a man of McConnell’s race and class could soar with the wings of the aviator. As Thomas J. Brown writes, “Remembrance of war from the late eighteenth century until the mid-twentieth century drew on a widely shared vocabulary, elements of which developed much earlier and parts of which were not unique to military contexts.”43 Viewers of this monument would have understood who in their society had the opportunities to be warriors like the aviator in the statue, and who they expected to be subject to such men. And the references to Icarus, too, himself a lost cause in many ways, align with notions of Southern masculinity that also limit participation in the ideals of the monument to people who look like McConnell.44

Modern visitors to grounds have had few complaints about “The Aviator” other than a few opinions that it is too ugly for UVA students to have to look at every day. Race only comes into the discussion when Borglum’s history of anti-Semitism and Ku Klux Klan membership have to be acknowledged.45 Though he created a famous statue to memorialize Lincoln, even named his son Lincoln, and would later criticize Hitler, Borglum’s views of the promise of American individuals to change the world clearly only expected white men to step into that role. It is unnecessary to mull over the complexities of his personality to understand that white supremacy rests at the heart of what individuals like the Aviator can achieve. His work at the massive Stone Mountain carving, too, showed a willingness to glorify the Confederacy and its Lost Cause myth whatever his complicated relationship with local members of the Klan. Still, none of this has tarnished the image of the “The Aviator,” to this date. It remains a beloved image of sacrifice and achievement for the UVA community.

In looking at the history and interpretation of the McConnell monument, it should be clear that the statue fits into a definite vision of the university held by its leadership, and that the memorial came about because of clear historical forces at work among the people of Charlottesville at the time. They sought to justify the sacrifices of the war that they knew was coming in 1917 and had already witnessed by 1919. In turning those experiences into a positive story about who they were, the university called on the next generation to continue to follow the same ideals and to seek the same education that would allow them to do that. The monument also fits into a larger story of Virginia’s role, especially Charlottesville’s role, in the creation of modern America, a story that is far grander than any one airman, but also much less available to many of the people of the city and the Commonwealth than it was to him. Icarus might be able to reach for the sun, which is inspirational in its grand drama, but only a few people could ever hope to be Icarus in this story and in this place. Any discussion of the history of the University of Virginia would do well to stress that the dream to achieve great things is still there, but that the path is now available to ever more people, and the definition of the Charlottesville community continues to evolve.

Bibliography

Daily Progress, Charlottesville, VA. June 10, 1919, 1A. https://search.lib.virginia.edu/sources/uva_library/items/uva-lib:2114651. Accessed December 6, 2021.

Daily Progress, Charlottesville, VA. June 11, 1919, 6C. https://search.lib.virginia.edu/sources/uva_library/items/uva-lib:2114658. Accessed December 6, 2021.

Alderman, Edwin Anderson. Virginia. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1916.

American Battle Monuments Commission. Cemeteries & Memorials. “Lafayette Escadrille Memorial Cemetery,” 2021. https://www.abmc.gov/Lafayette-Escadrille. Accessed December 5, 2021.

Autry, Robyn. “Elastic Monumentality? The Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial and Counterpublic Historical Space.” Social Identities 25, no. 2 (2019): 169–85.

Bardin, James C. “The University and the War.” Corks & Curls 31 (1918): 216–20.

Bohland, Jon D. “Look Away, Look Away, Look Away to Lexington: Struggles over Neo-Confederate Nationalism, Memory, and Masculinity in a Small Virginia Town.” Southeastern Geographer 53, no. 3 (2013): 267–95.

Borglum, Gutzon. “Imitation the Curse of American Art.” Brush and Pencil 19, no. 2 (1907): 50–62.

———. “The Truth of Effigies.” The Lotus Magazine 9, no. 3 (1917): 101–3.

Britton, Rick. “The Aviator.” MHQ : The Quarterly Journal of Military History 31, no. 3 (2019): 44–51.

Brown, Thomas J. “Monuments and Ruins: Atlanta and Columbia Remember Sherman.” Journal of American Studies 51, no. 2 (2017): 411–36.

Collins, Ross F. “Myth as Propaganda in World War I: American Volunteers, Victor Chapman, and French Journalism.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 92, no. 3 (2015): 642–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015573006.

Executive Committee of the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association. “A Statement by the Executive Committee of the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association: Concerning the Reasons Why It Was Necessary to Dismiss Gutzon Borglum.” March 14, 1925.

Flood, Charles Bracelen. First to Fly: The Story of the Lafayette Escadrille, the American Heroes Who Flew for France in World War I. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2015.

Johnson, Herbert W. “The Aero Club of America and Army Aviation, 1907-1916.” New York History 66, no. 4 (1985): 375–95.

Kelly, Matt. “UVA Honors Inspiration for ‘Wing Aviator’ Statue, 100 Years After His Death.” UVAToday: News. University of Virginia, March 14, 2017. https://news.virginia.edu/content/uva-honors-inspiration-winged-aviator-statue-100-years-after-his-death Accessed December 6, 2021.

McConnell, James R. Flying for France: With the American Escadrille at Verdun. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1917.

———. “James R. McConnell to Marcelle Guerin,” March 16, 1917. MSS 2104, Papers of James Rogers McConnell. Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Nelson, Louis P. “Object Lesson: Monuments and Memory in Charlottesville.” Buildings & Landscapes 25, no. 2 (2018): 17–35.

Samuels, Kathryn Lafrenz. “Deliberate Heritage: Difference and Disagreement After Charlottesville.” The Public Historian 41, no. 1 (2019): 121–32.

Schein, Richard H. “After Charlottesville: Reflections on Landscape, White Supremacy and White Hegemony.” Southeastern Geographer 58, no. 1 (2018): 10–13.

Smead, Susan. “The Aviator #002-5073.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. Virginia Department of Historic Resources, October 12, 2006.

University of North Carolina. DocSouth: Commemorative Landscape. “James Rogers McConnell Memorial, Carthage.” c. 2015. https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/265. Accessed December 5, 2021.

University of Virginia. “James Rogers McConnell Memorial Collections.” University of Virginia Library Online Exhibits. https://explore.lib.virginia.edu/exhibits/show/mcconnell. Accessed December 1, 2021.

———. “May Bring Aviator’s Body Here for Burial.” College Topics, March 30, 1917.

———. “Tablet Commemorating Service of James R. McConnell from French Republic.” University of Virginia Alumni News, January 1921, 140.

———. “The Aviator: Remembering James Rogers McConnell.” Notes from Under Grounds: Exibitions, April 17, 2017. https://smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/2017/04/10/the-aviator/. Accessed November 30, 2021.

US Congress. “Lafayette, We Are Here: The American Lafayette Escadrille,” Congressional Record Daily Edition, Washington D.C.:US Government Printing Office, 2018. H9701.

Van Landingham, Corey. “Antebellum.” Michigan Quarterly Review 56, no. 4 (2017): 477–501.

Wolfe, Brendan. “A Flight Forgotten: A Brief History of a Familiar Statue,” Virginia: The UVA Magazine 105, no. 3 (Fall 2016) 94-95.

Notes

-

University of Virginia, “The Aviator: Remembering James Rogers McConnell,” Notes from Under Grounds: Exibitions, April 17, 2017. https://smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/2017/04/10/the-aviator/. Accessed November 30, 2021. ↩

-

Rick Britton, “The Aviator.” MHQ : The Quarterly Journal of Military History 31, no. 3 (2019): 44–51. 46-47. ↩

-

James R. McConnell, Flying for France: With the American Escadrille at Verdun. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1917. 13. ↩

-

Britton, “Aviator,” 48. ↩

-

Charles Bracelen Flood, First to Fly: The Story of the Lafayette Escadrille, the American Heroes Who Flew for France in World War I, New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2015. 32. ↩

-

McConnell, Flying for France, 27. ↩

-

US Congress. “Lafayette, We Are Here: The American Lafayette Escadrille,” Congressional Record Daily Edition, Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/congressional/view/app-gis/congdaily/cr29no2018_dat-88. H9701. The record says that 51 died, but this appears to be an error based on the number buried at the monument in France. ↩

-

UVA, “The Aviator.” ↩

-

James Rogers McConnell to Paul Rockwell, September 4, 1916. See further letters to Rockwell and the collection finding aid for more details about how it affected his flying. University of Virginia. University of Virginia Library Exhibits, “James Rogers McConnell Memorial Collections,” https://explore.lib.virginia.edu/exhibits/show/mcconnell. Accessed December 1, 2021. ↩

-

James R. McConnell to Marcelle Guérin, March 16, 1917. James Rogers McConnell Memorial Collections, Accession #2104, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va. His last letter to her. ↩

-

Britton, “Aviator,” 50. ↩

-

McConnell, Flying for France, 64. ↩

-

McConnell, Flying for France, 82. ↩

-

Britton, “Aviator,” 51. ↩

-

University of Virginia, “May Bring Aviator’s Body Here for Burial,” College Topics, March 30, 1917. 4. ↩

-

James C. Bardin, “The University and the War.” Corks & Curls 31 (1918): 216–220. 220. ↩

-

Bardin, “University and War,” 217. ↩

-

UVA, “Aviator’s Body,” 4. ↩

-

University of North Carolina, DocSouth: Commemorative Landscape, “James Rogers McConnell Memorial, Carthage,” c. 2015. https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/265. Accessed December 5, 2021. See also descriptions in the James Rogers McConnell Memorial Collection, #2104, at the University of Virginia. ↩

-

University of Virginia. “Tablet Commemorating Service of James R. McConnell from French Republic.” University of Virginia Alumni News, January 1921, 140. ↩

-

American Battle Monuments Commission, Cemeteries & Memorials, “Lafayette Escadrille Memorial Cemetery,” 2021. https://www.abmc.gov/Lafayette-Escadrille Accessed December 5, 2021. ↩

-

Susan Smead, “The Aviator #002-5073,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, October 12, 2006. ↩

-

Herbert W. Johnson, “The Aero Club of America and Army Aviation, 1907-1916.” New York History 66, no. 4 (1985): 375–95. 378. The Aero Club had been central for getting Congress to appropriate funds for the US air service in 1916 that would be the basis for later American pilot training for the war. ↩

-

Gutzon Borglum, “Imitation the Curse of American Art,” Brush and Pencil 19, no. 2 (1907): 50–62. 56. ↩

-

Edwin Anderson Alderman, Virginia, New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1916. ↩

-

Alderman, Virginia, 51. “All while acting honorably,” writes Alderman. Also sees that in Lee a “figure of quiet strength and invincible rectitude and utter self-surrender may be discerned the complete drama of a great stock.” 47. ↩

-

Bardin, “University and War,” 216-217. ↩

-

Daily Progress, Charlottesville, VA, June 10, 1919, 1A. https://search.lib.virginia.edu/sources/uva_library/items/uva-lib:2114651. Accessed December 6, 2021. ↩

-

Daily Progress, Charlottesville, VA, June 11, 1919, 6C. https://search.lib.virginia.edu/sources/uva_library/items/uva-lib:2114658. Accessed December 6, 2021. ↩

-

Matt Kelly, “UVA Honors Inspiration for ‘Wing Aviator’ Statue, 100 Years After His Death,” UVAToday: News, University of Virginia, March 14, 2017. https://news.virginia.edu/content/uva-honors-inspiration-winged-aviator-statue-100-years-after-his-death Accessed December 6, 2021. ↩

-

Ross F. Collins, “Myth as Propaganda in World War I: American Volunteers, Victor Chapman, and French Journalism,” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 92, no. 3 (2015): 642–661. 644-645. ↩

-

Collins, “Myth as Propaganda,” 654. ↩

-

Corey Van Landingham, “Antebellum.” Michigan Quarterly Review 56, no. 4 (2017): 477-501. 481. ↩

-

Kathryn Lafrenz Samuels, “Deliberate Heritage: Difference and Disagreement After Charlottesville.” The Public Historian 41, no. 1 (2019): 121–132. 121. ↩

-

Louis P. Nelson, “Object Lesson: Monuments and Memory in Charlottesville,” Buildings & Landscapes 25, no. 2 (2018): 17–35. 18. ↩

-

Nelson, “Object Lesson,” 22. ↩

-

Nelson, “Object Lesson,” 27. ↩

-

Richard H. Schein, “After Charlottesville: Reflections on Landscape, White Supremacy and White Hegemony.” Southeastern Geographer 58, no. 1 (2018): 10–13. 11-12. ↩

-

McConnell, Flying for France, 54. “On the way up I passed a cantonment of Senegalese. About twenty of ‘em jumped up from the bench they were sitting on and gave me the hell of a salute. Thought I was a general because I was riding in a car, I guess. They’re the blackest niggers you ever saw. Good-looking soldiers. Can’t stand shelling but they’re good on the cold steel end of the game.” ↩

-

Nelson, “Object Lesson,” 24. ↩

-

UVA, “McConnell Collections.” ↩

-

Nelson, “Object Lesson,” 21. ↩

-

Thomas J. Brown, “Monuments and Ruins: Atlanta and Columbia Remember Sherman.” Journal of American Studies 51, no. 2 (2017): 411–436. 435. ↩

-

Jon D. Bohland, “Look Away, Look Away, Look Away to Lexington: Struggles over Neo-Confederate Nationalism, Memory, and Masculinity in a Small Virginia Town,” Southeastern Geographer 53, no. 3 (2013): 267–295. 268. ↩

-

“Borglum himself was a complicated character.” Brendan Wolfe, “A Flight Forgotten: A Brief History of a Familiar Statue,” Virginia: The UVA Magazine 105, no. 3 (Fall 2016) 94-95. See also Van Landingham, “Antebellum,” 491. ↩