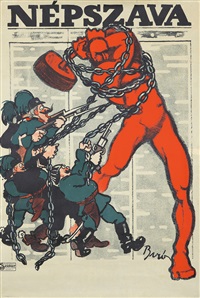

The Red Man

The Red Man is the name of the hammer-weilding figure in the propaganda poster at the focus of this project. It turns out that he was an icon of early 20th century, European propaganda. He appeared in several propaganda pieces in the first three decades of the 20th century, and artists and political movements at that time adapted his image for their own purposes. While this project is not about the politics of propaganda, it is impossible to tell the history of the Red Man without addressing the politics that inspired Mihály Biró to create him and shaped how people used him.

Red Man's first appearance was in 1911 on the cover of a left-wing Hungarian newspaper named Népszava, which translates into English as The People's Word. Népszava had been the official newspaper of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party going back to 1873. Mihály Biró, whose half-brother was the editor, had joined the newspaper that year after having studied art Central Europe and Britain. The Red Man appeared again on a poster in 1912 advertizing Népszava and then on another cover in 1913. A year later, Biró used a varation of the Red Man in chains and fighting gendarmes on yet another cover of Népszava as a protest against censorship. By that time, Biró's Red Man had became so famous in Hungary that it became a symbol of the Social Democratic Party and the labor movement.

Soon, the Red Man began to appear more widely in Hungary and internationally. Temporary statues of him appeared across Budapest on May Day in 1918. He had become a national symbol for that holiday, which was a celebration of the working class. In 1920, the German Communist Party produced a propaganda poster with a red fist - an illusion to Biró’s Red Man - smashing a table at the Paris peace conference in 1919 that marked the final settlement of WWI. By 1922, he appeared in pamphlets in China, Britain, and Italy. The international Left continued to use The Red Man as a political symbol, in particular in Vienna and Berlin, until the middle of the 1920s.

Curiously, the Red Man also inspired criticism of the political causes Mihály Biró supported. A satirical version of the Red Man appeared in Germany as far back as 1911 in The Social Democratic Party of Germany’s satire magazine Der Wahre Jacob. In that version, the Red Man stands over the rubble of a factory and warns workers that it is better to be “smashed by the machine than to starve,” which suggests to German workers that they should ignore the political message of Mihály Biró’s propaganda. Likewise, the military dictatorship that gained power in Hungary after WWI financed artists to make posters using variations of the Red Man. One of those posters used anti-Semitic messaging to encourage revenge for supposed atrocities committed by the Left.

Bibliography

“Communicating Europe: Hungary Manual Information and Contacts on the Hungarian Debate on EU Enlargement.” 2010. https://www.esiweb.org/pdf/enlargement_debates_manual_hungary.pdf.

Dent, Bob. Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic. 1st ed. London: Pluto Press, 2018.

Simmons, Sherwin. “Mihály Biró’s Népszava Poster and the Emergence of Tendenzkunst.” In Work and the Image, 133–151. 1st ed. United Kingdom: Routledge, 2000.