Analysis and Interpretation

The Red Man

The Red Man is the name of the hammer-wielding figure in the propaganda poster that is the subject of this project. He became an icon of early 20th century propaganda as artists and political movements at that time adapted his image for their own purposes. While this project is not about the politics of propaganda, it is impossible to tell the history of the Red Man and Mihály Biró's propaganda poster without addressing the politics that inspired Biró and shaped how people used his symbol.

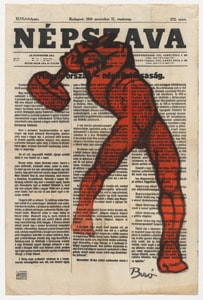

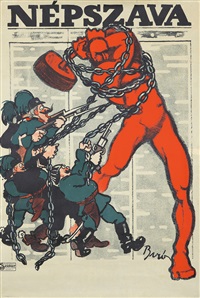

The Red Man's first appearance was in 1911 on the cover of a left-wing Hungarian newspaper named Népszava, which translates into English as The People's Word.1 Népszava had been the official newspaper of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party going back to 1873.2 Mihály Biró, whose half-brother was the editor, joined the newspaper that year after studying art in Central Europe and Britain.3 The Red Man appeared again on a poster in 1912 advertising Népszava and then on another cover of Népszava in 1913.4 A year later, Biró used a variation of the Red Man in chains fighting gendarmes on a third cover of Népszava as a protest against censorship.5 By that time, his Red Man had became so famous in Hungary that it became a symbol of the Social Democratic Party and the labor movement.6

Soon, the Red Man began to appear more widely in Hungary and internationally. Temporary statues of him appeared across Budapest on May Day in 1918.7 He had become a national symbol for that holiday, which was a celebration of the working class.8 In 1920, the German Communist Party produced a propaganda poster with a red fist - an illusion to Biró’s Red Man - smashing a table at the Paris peace conference in 1919 that marked the final settlement of WWI.9 By 1922, he appeared in pamphlets in China, Britain, and Italy. The international Left continued to use The Red Man as a political symbol, in particular in Vienna and Berlin, until the middle of the 1920s.10

Surprisingly, the Red Man also inspired criticism of the political causes Mihály Biró supported. A satirical version of the Red Man appeared in Germany as far back as 1911 in The Social Democratic Party of Germany’s satire magazine Der Wahre Jacob.11 In that version, he stands over the rubble of a factory and warns workers that it is better to be “smashed by the machine than to starve,” which suggests to German workers that they should ignore Mihály Biró’s propaganda.12 Likewise, the military dictatorship that gained power in Hungary after WWI financed artists to make posters using variations of the Red Man.13 One of those posters used anti-Semitic messaging to encourage revenge for supposed atrocities committed by the Left.14

Comparing Mihály Biró and Egon Schiele

Case study one makes three comparisons between Mihály Biró's propaganda poster May 1st, 1919 and Egon Schiele’s painting Fighter. Before discussing those comparisons, an introduction to Schiele would be useful. As the Museum of Modern Art’s page dedicated to him explains, he was an Austrian painter born in 1890, who began studying art at sixteen years old in Vienna and was mentored by Gustav Klimt.15 Over his career, Schiele created portraits famous for their incisive portrayal of their subject matter and for the presentation of bodies in expressive, contorted, and sexually explicit ways.16 He liked working with water colors and printmaking, the latter of which he felt was lucrative, but overly technical.17 Schiele passed away at just twenty-eight years old shortly after his pregnant wife’s death as a result of an influenza pandemic.18

Case study one’s comparisons of Mihály Biró’s propaganda poster and Egon Schiele’s painting focus on ways that both works of art connect with audiences. The first two comparisons highlight a sense of implied motion in the the body language and posture of the subjects of both works. The third comparison highlights how the facial expressions of those subjects seem to stare at or in the direction of viewers. These suggestions of motion and eye contact, as this analysis will discuss in more detail below, are ways that Biró and Schiele engage with their audiences.

Stylistically speaking, the connections that Biró’s and Schiele’s works create with an audience fit an early 20th century style of art called Expressionism with which Schiele is associated. The Museum of Modern Art’s page about German Expressionism, for instance, lists him as an Expressionist.19 As for what Expressionism means, a useful introduction appears in Gateways to Art: Understanding The Visual Arts by Debra J. DeWitte, Ralph M. Larmann, and M. Kathryn Shields. According to the book, Expressionism involves exploring emotions by portraying them to their fullest intensity by emphasizing and exaggerating a painting’s subject matter.20 Expressionists, the book’s authors argue, aim to depict “inner states of feeling” on a canvas, rather than simply reproduce how something looks.21

The three comparisons in case study one reveal Expressionist elements in Schiele’s Fighter. The fighter’s body language, posture, and stare create a connection with viewers. As the comparisons in this project’s first case study explain, those elements suggest the subject’s motion and, through the look on his face, emotional content, with which they can connect. Viewers, then, can speculate about inner state of the fighter. For instance, they might interpret the painting as capturing the moment when the fighter turns and notices the viewer. Alternatively, the audience may take a more aggressive interpretation and ask if the fighter is about to turn towards them as if they are an opponent or a target. Whatever reaction they may have, the painting invites speculation about the fighter’s intentions and emotions, which are inner states and of special interest to Expressionist painters.

Mihály Biró’s poster May 1st, 1919 also invites speculation about the inner state of its subject, the Red Man. Case study one’s comparisons point out elements of the poster that create connections with viewers: the suggestion of motion as the Red Man leans back, with a wide stance, and prepares to swing his hammer, and the look on his face leading viewers to speculate about where he is looking. Those elements taken together may lead viewers to interpret the scene in the poster in different ways. They might think about the Red Man as a worker looking downward as he prepares to strike something in front of his feet, such as a bolt that needs to be hammered into a piece of steel. Another interpretation is more aggressive, were the Red Man is looking at and preparing to strike the viewer, which can be a reminder of the power of workers and the working class.

This idea that the Red Man’s motion is ambiguous comes from a commentary by Sherwin Simmons’ in Work and the Image: “[Biró’s] poster for Nepszava and subsequent use of the Red Man [made] . . . the hammer's swing ambiguous, raising the possibility of revolutionary violence and destruction by the masses.”22 In this case, Simmons brings Biró’s politics into the interpretation, but, for case study one, what is more important is the range of possibilities for interpreting the Red Man’s swing.

Not all interpretations necessarily communicate a message in line with Biró’s socialism. For example, in a non-political sense, a viewer might interpret his poster as a commentary on the human condition or the struggle against adversity. Another viewer might think about the Red Man’s swing as a celebration of manual labor. Yet another interpretation might consider the swing and the way Biró paints the Red Man as a commentary on masculinity or gender. These are, of course, only a few examples of how to interpret Biró’s poster without following his socialist politics.

Click here for the Museum of Modern Art’s page dedicated to German Expressionism to learn more about that style and view several famous examples of it.

Click here for the MoMA’s page about Egon Schiele to learn about his life, to see examples of his work, and for a short list of books about him.

To visit or return to this project’s analysis of Mihály Biró’s poster and Egon Schiele’s painting, click here.

Comparing Mihály Biró and Käthe Kollwitz

Case study two compares the work of two famous artists from the beginning of the 20th century, Mihály Biró and Käthe Kollwitz. Because this project has already introduced Biró, this commentary will begin with an introduction to Kollwitz, who was a talented artist who was not shy about expressing her ethics through her work. According to the Museum of Modern Art’s page about her, Kollwitz was born in 1867 in Prussia and began her artistic career as a painter.23 She admired the working class and dedicated her art to the oppressed and poor.24

By 1890, Kollwitz had switched to printmaking, so she could produce social criticism, and also began to create woodcuts, sculptures, and etchings.25 Decades later, after her son’s death during WWI, she decided to become a pacifist and focus on themes in her art about sacrifice and mourning.26 Her hard work paid off because, in 1919, she became the first woman elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts.27 Unfortunately, the Nazis decided to expel her from the organization years later.28 Kollwitz died in 1945, two weeks before Germany surrendered in WWII.29

The comparisons case study two makes between Mihály Biró’s propaganda poster, May 1st, 1919, and Käthe Kollwitz’s print, Losbruch (Outbreak) from the series Peasants’ War, demonstrate that both works of art are attempts to engage with audiences, which is a goal of Expressionism. Kollwitz happens to be associated with Expressionism, which, as case study one pointed out, aims to depict “inner states of feeling” in a work of art, not simply how a subject looks. As for Kollwitz’s association with Expressionism, the Museum of Modern Art’s page about her lists her style as German Expressionist and her page is part of a digital collection dedicated to German Expressionism.30 31

The first comparison in case study two considers how Biró and Kollwitz use the suggestion of motion in their works. Going back to case study one, the figure in Biró’s poster, named the Red Man, appears frozen at the moment before he is about to swing his hammer. Likewise, Kollwitz’s print captures a mass of peasants beginning to move forward. She suggests this by the way she portrays the front of the army seeming to rush ahead and the peasants further back standing or walking. It is as if the front ranks are beginning a charge, and everyone behind them has not yet started to pick up their pace.

The second comparison brings attention to the way Biró and Kollwitz divide their canvases. When one clicks the second comparison button on case study two’s page, lines appear on both works based on the ways the artists placed their subject matter. These lines bring to mind the idea of “communicative lines” in Gateways to Art: Understanding The Visual Arts, the book that case study one uses to define Expressionism.32 Communicative lines, the book explains, can guide viewers’ attention and suggest certain feelings.33 Diagonal lines imply “action, motion, and change,” which fits the presentation of the peasant army marching forward in Kollwitz’s print and intersects a second diagonal line marked by the woman in the foreground.34

In contrast, the lines in Biró’s poster suggest emotions that conflict with each other. There is a diagonal line that follows the Red Man‘s posture and intersects with a horizontal line near his feet. Gateways to Art suggests that horizontal lines imply “calmness and passivity.”35 What does this intersection suggest about the poster?

While it is impossible to know what Biró had in mind as he prepared his poster, two things are worth keeping in mind: 1) the diagonal and horizontal lines in his poster imply contrary feelings and 2) the Red Man’s hammer looks like it is about to swing downward at the horizontal line, so it seems to threaten or conflict with the calmness and passivity that the horizontal line implies. These conflicting feelings, inspired by intersecting lines, may make viewers of Biró’s poster feel conflicted and apprehensive.

The last comparison in case study two has to do with the facial expressions on Biró’s Red Man and Kollwitzs’ army of peasants. Perhaps more than the first two comparisons, these faces invite viewers to speculate about the feelings and intentions of the figures that appear in both works of art. Case study one describes how the direction the Red Man is looking invites viewers to ask what he is planning to hit with his hammer: is he aiming for something in front of his feet or am I, the viewer of the poster, his target? Kollwitz’s print includes several intriguing faces. The expressions on the peasants at the front look intense, with mouths open and teeth baring. On the other hand, the face that one can see most clearly in the print, which appears further back in the ranks, looks calm, and viewers may interpret his face as a sign of determination and conviction.

Of course, speculating about Kollwitz’s army’s facial expressions should take into account the historical event she was memorializing in her print. The Nasher Museum at Duke University describes her print as, “a universalized depiction of the 1525 peasants’ revolt against feudalism that took place in the German-speaking areas of Central Europe.”36 With that in mind, viewers can ask themselves how the peasants’ facial expressions fit such a dramatic event.

Whether viewers of Mihály Biró’s and Käthe Kollwitz’s works agree with the interpretations of case study two’s comparisons or not, those comparisons at least demonstrate that one can interpret Biró’s poster without having to rely on its political message. They focus on ways that his poster is similar to Kollwitz’s print, which is a work of Expressionist art that attempts to depict the inner, emotional life of a peasant army. Case study two, then, has interpreted Biró’s poster as an attempt to depict the inner life of its subject.

Click here for the Museum of Modern Art’s page dedicated to German Expressionism to learn more about that style and view several famous examples of it.

Click here for the MoMA’s page about Käthe Kollwitz to learn about her life, to see examples of her work, and for a short list of books about her.

To visit or return to this project’s analysis of Mihály Biró’s poster and Käthe Kollwitz's print, click here.

Bibliography

Communicating Europe: Hungary Manual Information and Contacts on the Hungarian Debate on EU Enlargement. (Budapest and Berlin: European Stability Initative, December 2010), https://www.esiweb.org/pdf/enlargement_debates_manual_hungary.pdf.

Dent, Bob. Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic. 1st ed. London: Pluto Press, 2018.

DeWitte, Debra J., Ralph M. Larmann, and M. Kathryn Shields. Gateways to Art, 2018.

“German Expressionism: Works From The Collection,” MoMA, 2011, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/curated_ge/artists.html.

Hess, Heather. “Egon Schiele: Austrian, 1890–1918.” The Museum of Modern Art, 2011. Accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-5215_thumbs.html.

Hess, Heather. “Käthe Kollwitz: German, 1867–1945.” The Museum of Modern Art, 2011. Accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-3201.html.

Mihály Biró, Bitangok! Ezt akartátok?, Budapest Poster Gallery, retrieved November 29th, https://budapestposter.com/posters/5755

Mihály Biró, Népszava: Magyarország népköztársaság, The Museum of Modern Art, retrieved November 29th, 2023, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/126205?artist_id=36589&page=1&sov_referrer=artist

Mihály Biró, The Charnel-House, retrieved November 29th, https://i0.wp.com/thecharnelhouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/mihacc81ly-birocc81-necc81pszava-1914-necc81pszava-means-the-voice-of-the-people.jpeg

Simmons, Sherwin. “Mihály Biró’s Népszava Poster and the Emergence of Tendenzkunst.” In Work and the Image, 133–151. 1st ed. United Kingdom: Routledge, 2000.

References

1. Dent, Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, 50.

2. Communicating Europe: Hungary Manual Information and contacts on the Hungarian debate on EU enlargement, (Budapest and Berlin: European Stability Initative, December 2010), 8.

3. Sherwin Simmons, “Mihály Biró’s Népszava Poster and the Emergence of Tendenzkunst*,” in Routledge eBooks, 2019, 133–51, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315189444-8, 134.

4. Dent, Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, 50.

5. Dent, Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, 50.

6. Dent, Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, 50.

7. Dent, Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, 50.

8. Dent, Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, 50.

9. Simmons, “Mihály Biró’s Népszava Poster and the Emergence of Tendenzkunst*,” 2019, 134.

10. Dent, Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, 50.

11. Simmons, “Mihály Biró’s Népszava Poster and the Emergence of Tendenzkunst*,” 2019, 134.

12. Dent, Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, 50.

13. Dent, Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, 50.

14. Simmons, “Mihály Biró’s Népszava Poster and the Emergence of Tendenzkunst*,” 2019, 134

15. Heather Hess, “Review of Egon Schiele Austrian, 1890–1918,” MoMA, 2011, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-5215_thumbs.html.

16. Heather Hess, “Review of Egon Schiele Austrian, 1890–1918,” MoMA, 2011, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-5215_thumbs.html.

17. Heather Hess, “Review of Egon Schiele Austrian, 1890–1918,” MoMA, 2011, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-5215_thumbs.html.

18. Heather Hess, “Review of Egon Schiele Austrian, 1890–1918,” MoMA, 2011, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-5215_thumbs.html.

19. “German Expressionism: Works From The Collection,” MoMA, 2011, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/curated_ge/artists.html.

20. Debra J. DeWitte, Ralph M. Larmann, and M. Kathryn Shields, Gateways to Art, 2018, 521.

21. DeWitte, Larmann, and Shields, Gateways to Art, 2018, 521.

22. Simmons, “Mihály Biró’s Népszava Poster and the Emergence of Tendenzkunst*,” 2019, 144.

23. Heather Hess, “Käthe Kollwitz German, 1867–1945,” The Museum of Modern Art, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-3201.html.

24. Heather Hess, “Käthe Kollwitz German, 1867–1945,” The Museum of Modern Art, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-3201.html.

25. Heather Hess, “Käthe Kollwitz German, 1867–1945,” The Museum of Modern Art, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-3201.html.

26. Heather Hess, “Käthe Kollwitz German, 1867–1945,” The Museum of Modern Art, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-3201.html.

27. Heather Hess, “Käthe Kollwitz German, 1867–1945,” The Museum of Modern Art, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-3201.html.

28. Heather Hess, “Käthe Kollwitz German, 1867–1945,” The Museum of Modern Art, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-3201.html.

29. Heather Hess, “Käthe Kollwitz German, 1867–1945,” The Museum of Modern Art, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-3201.html.

30. Heather Hess, “Käthe Kollwitz German, 1867–1945,” The Museum of Modern Art, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-3201.html.

31. “German Expressionism: Works From The Collection,” The Museum of Modern Art, accessed November 28, 2023, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/curated_ge/index.html.

32. Debra J. DeWitte, Ralph M. Larmann, and M. Kathryn Shields, Gateways to Art, 2018, 49.

33. Debra J. DeWitte, Ralph M. Larmann, and M. Kathryn Shields, Gateways to Art, 2018, 49.

34. Debra J. DeWitte, Ralph M. Larmann, and M. Kathryn Shields, Gateways to Art, 2018, 49.

35. Debra J. DeWitte, Ralph M. Larmann, and M. Kathryn Shields, Gateways to Art, 2018, 49.

36. “Losbruch (Outbreak) from the Series Peasants’ War,” n.d., https://emuseum.nasher.duke.edu/objects/9221/losbruch-outbreak-from-the-series-peasants-wa.

37. Mihály Biró, Népszava: Magyarország népköztársaság, The Museum of Modern Art, retrieved November 29th, 2023, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/126205?artist_id=36589&page=1&sov_referrer=artist

38. Mihály Biró, The Charnel-House, retrieved November 29th, https://i0.wp.com/thecharnelhouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/mihacc81ly-birocc81-necc81pszava-1914-necc81pszava-means-the-voice-of-the-people.jpeg

39. Mihály Biró, Bitangok! Ezt akartátok?, Budapest Poster Gallery, retrieved November 29th, https://budapestposter.com/posters/5755