Recent Findings

Community Connectedness

At the start of incarceration and just before being released, we asked inmates to tell us how connected they felt to the community at large (e.g., people who are not incarcerated and don’t commit crimes) and the criminal community (e.g., people who are in the community or incarcerated who commit crimes).

We found that on average, connectedness to both communities did not change during incarceration (Folk et al., in preparation). When considering individual differences, we found that younger inmates and those who were more likely to experience guilt tended to become more connected to the criminal community during incarceration.

We also found that people who felt highly connected to the criminal community were more likely to commit crimes and/or be arrested during their first year in the community (Folk et al., 2016). People who felt highly connected to the community at large were more positively adjusted in the community. For example, they were more likely to be legally employed, have a stable living situation, and to support themselves through a job or savings.

References:

Folk, J. B., Mashek, D., Tangney, J., Stuewig, J., & Moore, K. (2016). Connectedness to the criminal community and the community at large predicts 1 year post-release outcomes among felony offenders. European Journal of Social Psychology, 46, 341-355.

Folk, J. B., Mashek, D., Stuewig, J., Tangney, J., Moore, K., & Blasko, B. (under review). Changes in jail inmates’ community connectedness across the period of incarceration.

Racial Differences in Treatment Seeking

Need for Treatment, Treatment Seeking, and Treatment Enrollment in a Jail Sample:

Race Differences in Psychological Treatment Seeking Disappear During Incarceration

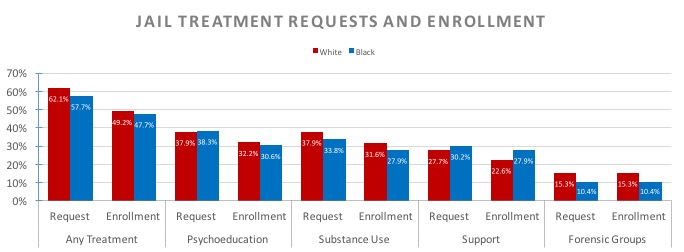

Shortly after incarceration, 229 Black and 185 White “general population” jail inmates (e.g., not in segregation or forensic housing) were asked about their psychological symptoms. More than half (63%) reported clinically significant symptoms of mental illness. There was no difference between Black and White inmates in the overall rate of mental illness symptoms.

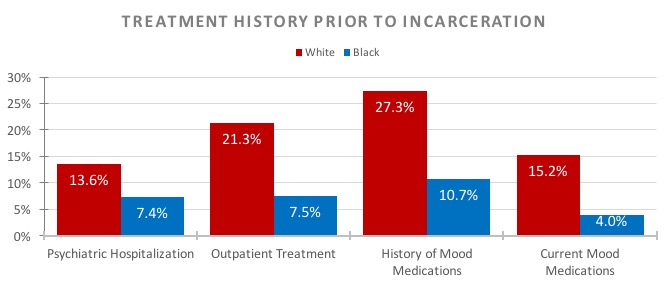

There were race differences in mental health treatment history before jail. Black inmates were less likely than White inmates to have received mental health treatment prior to incarceration.

However, there were no race differences in requests for treatment or enrollment in treatment during inmates’ time in jail. During incarceration, Black and White inmates were equally likely to request and to be enrolled in psycho-educational (e.g., anger management), substance abuse treatment (e.g., Alcoholics/Narcotics Anonymous), support groups, and forensic services. (Youman, Drapalski, Stuewig, Bagley, & Tangney, 2010).

Reference:

Youman, K., Drapalski, A., Stuewig, J., Bagley, K., & Tangney, J. (2010). Race differences in psychopathology and disparities in treatment seeking: Community and jail-based treatment-seeking patterns. Psychological Services, 7, 11-26. doi: 10.1037/a0017864

Strategic Jail Intervention

Strategic Delivery of Jail-Based Interventions

Currently, many jails miss out on the window of opportunity to treat high need individuals. One barrier to jail-based treatment is that few treatment programs have been designed with the needs of jail inmates and the characteristic of the jail environment in mind. Jail inmates come and go with little warning, due to bond outs, reclassifications, transfers, and such. Wanting to help, staff feels pressed to enroll whomever they can, whenever they can – often as early as they can. Treatment requiring multiple sessions over multiple weeks typically encounters high dropout rates (sometimes as high as 90%; Krebs, Brady & Laird, 2003) as participants leave the facility for various reasons. Furthermore, resources in jails are often scarce. While targeting treatment to inmates based on individual risk, need and responsivity is important (RNR; Andrews & Bonta, 2010), we argue that in jail populations, it is also crucial to consider an inmate’s stage of incarceration and projected time left in the facility, as well as the treatment’s length.

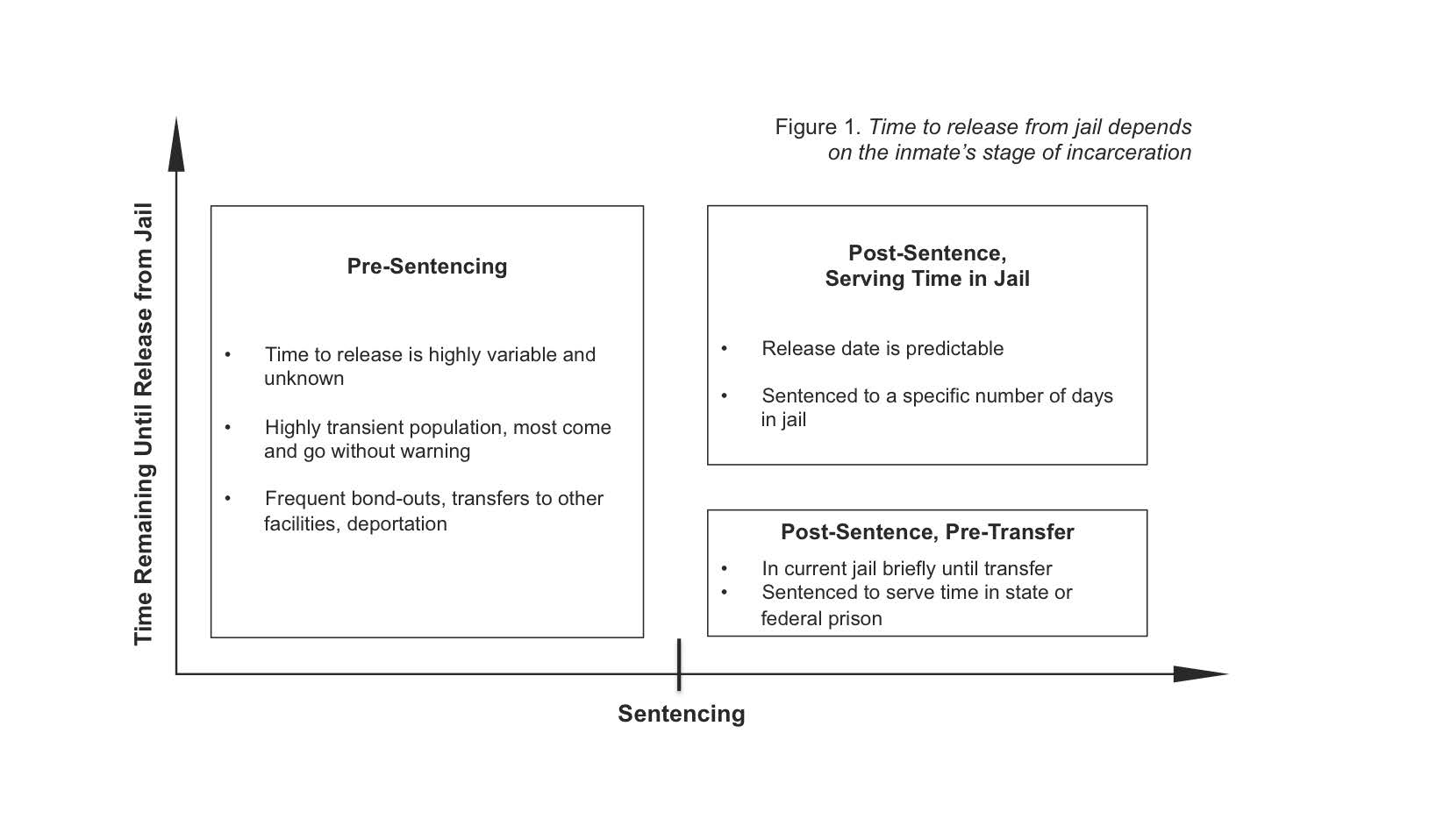

Three Types of Jail Inmates

Figure 1 illustrates the three types of jail inmates we have identified: pre-sentencing inmates, post-sentencing inmates who have been sentenced to serve time in jail, and post-sentencing inmates who are awaiting transfer to a state or federal prison. Pre-sentencing inmates are a very transient population with unpredictable release dates due to frequent bond-outs and transfers to other facilities. Post-sentencing/pre-transfer inmates, who have been sentenced to serve their time in prison, generally do not remain at the jail very long post-sentencing, but this is also variable and unpredictable. However, post-sentencing inmates sentenced to serve their time in jail DO generally have a predictable release date, which is anywhere from days to a year in the future.

The Right Treatment at the Right Time: Strategic Delivery of Jail-Based Interventions (SDJI)

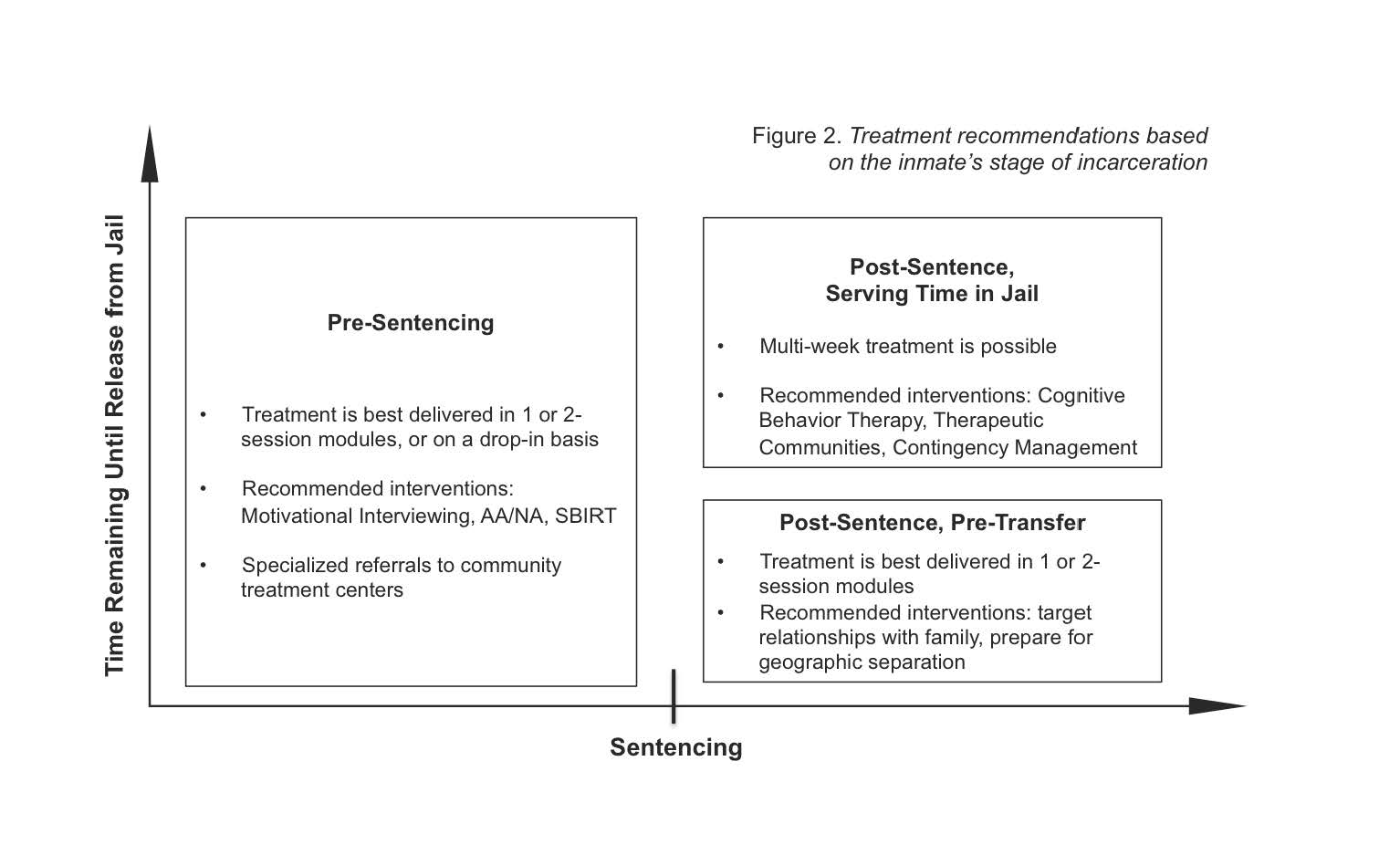

We propose a model of Strategic Delivery of Jail-Based Interventions (SDJI; Tangney et al., 2015). In this model, we argue that to maximize jail treatment’s effectiveness and efficiency, treatment programs should match inmates to treatment based not only on risks and needs, but also on treatment length, stage of incarceration, and projected time left in facility. For example, interventions for pre-sentence inmates should be delivered in short, standalone modules and should involve referrals to relevant community providers (see Figure 2). Longer, multi-week treatments should be reserved for post-sentencing inmates who are serving time at the jail and have a known release date months into the future. SDJI maximizes the number of inmates able to complete multi-week treatment by reserving this treatment for inmates with a known release date, instead of making limited treatment enrollment equally available to all inmates regardless of the likelihood they will be around long enough to complete it.

This approach also provides an opportunity to address the divergent needs of inmates at various stages of the criminal justice process. For example, for inmates that are pre-sentencing and may soon be released into the community, motivational interviewing as well as specialized referrals to community treatment centers may be especially relevant. For those that are post-sentencing and awaiting transfer to prison, interventions facilitating family communication may be helpful, as these inmates will likely have to endure geographical separation from their family for several years. Inmates that are post-sentencing and will be serving their sentence at the jail have the ability to complete evidence-based, multi-week interventions (e.g., cognitive-behavior therapy, contingency management, therapeutic communities) to address their individual criminogenic needs.

Implementation of SDJI: One Success Story

We used components of Strategic Delivery of Jail-Based Interventions (SDJI) in order to reduce involuntary treatment dropout in our evaluation of an 8-week victim impact group intervention (Folk et al., 2016). Specifically, we used the following inclusion criteria to screen inmates for eligibility into the intervention: (1) post-sentencing, (2) due to be released after program completion date, (3) no existing detainers or holds for another facility or for immigration services, (4) no orders to be kept separate from three or more inmates, and (5) miscellaneous other factors, such as eligibility for work release, that could contribute to inmates’ ability to complete the program. By using elements of SDJI, we were successful in minimizing dropout; 89% of participants in the 8-week program completed treatment (Folk et al., 2016). We believe that other jail programs in different facilities may obtain higher treatment completion rates and maximize program efficiency by using SDJI.

References:

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). Rehabilitating criminal justice policy and practice. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 16(1), 39-55. doi: 10.1037/a0018362

Folk, J. B., Blasko, B. L., Warden, R., Schaefer, K., Ferssizidis, P., Stuewig, J., & Tangney, J. P. (2016). Feasibility and acceptability of an impact of crime group intervention with jail inmates. Victims & Offenders, 11(3), 436-454.

Krebs, C. P., Brady, T., & Laird, G. (2003). Jail-based substance user treatment: An analysis of retention. Substance Use & Misuse, 38(9), 1127 – 1258.

Tangney, J. P., Daylor, J. M., Heigel, C., Warden, R., & Stuewig, J. (2015). Strategic jail intervention: The right treatment, at the right time, in the right timeframe. Poster presented at the 3rd Annual North American Correctional and Criminal Justice Psychology Conference, Ottawa, ON, Canada.