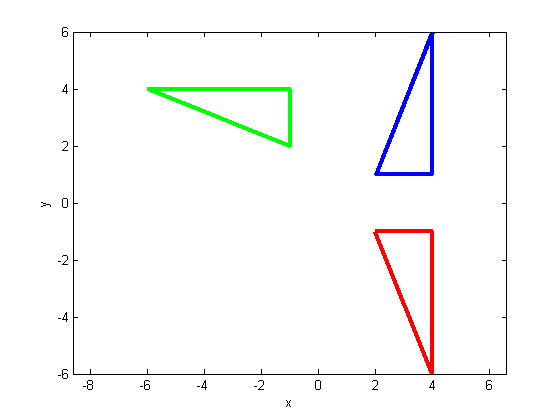

% Triangle (repeating points allow it to be plotted) tr = [2,1; 4,1; 4,6; 2,1]'; % Plot the original triangle in blue plot(tr(1,:), tr(2,:), 'b', 'LineWidth', 3); set(gcf, 'color', 'w') xlabel('x') ylabel('y') axis equal; hold on; % Let the angle of rotation be 90degrees theta = 90; % The first rotation matrix T1 = [cosd(theta), -sind(theta); sind(theta), cosd(theta)]; % Determinant is 1 disp(strcat('det(T1)=', num2str(det(T1)))); % Triangle rotated with T1 plotted in green tr1 = T1*tr; plot(tr1(1,:), tr1(2,:), 'g', 'LineWidth', 3); hold on; % The second rotation matrix T2 = [sind(theta), cosd(theta); cosd(theta), -sind(theta)]; % Determinant is -1 disp(strcat('det(T2)=', num2str(det(T2)))); % Triangle rotated with T2 plotted in red tr2 = T2*tr; plot(tr2(1,:), tr2(2,:), 'r', 'LineWidth', 3); % COMMENTS: % T2 is NOT a rigid body transformation because it does not preserve the % orientation of the triangle. The difference between T1 and T2 is that % the x-axis and the y-axis are switched, which turns the normal % (right-handed) coordinate system into a left-handed one. If we imagine % the triangle as a tile, T2 requires us to flip the tile upside down, % thus leaving the plane of rotation.

det(T1)=1 det(T2)=-1