|

| by

Robert Browning |

| |

|

|

| I

am poor brother Lippo, by your leave! |

|

Below are images of some relevant paintings.

Some are links to larger versions. |

| You need

not clap your torches to my face. |

|

| Zooks,

what’s to blame? you think you see a monk! |

|

What, ’tis

past midnight, and you go the rounds,

|

|

|

| And here

you catch me at an alley’s end |

|

|

| Where sportive

ladies leave their doors ajar? |

|

|

|

The Carmine’s my cloister: hunt it up, |

|

|

| Do,

— harry out, if you must show your zeal, |

|

Cosimo de’Medici

Cosimo de’Medici

(16th century posthumous portrait by Pontormo)

Click for larger image

|

| Whatever

rat, there, haps on his wrong hole, |

|

| And nip each

softling of a wee white mouse, |

10 |

| Weke, weke,

that’s crept to keep him company! |

|

| Aha, you

know your betters! Then, you’ll take |

|

| Your hand

away that’s fiddling on my throat, |

|

| And please

to know me likewise. Who am I? |

|

| Why, one,

sir, who is lodging with a friend |

|

| Three streets

off — he’s a certain . . . how d’ye call? |

|

| Master

— a . . . Cosimo of the Medici, |

|

| I’

the house that caps the corner. Boh! you were best! |

|

| Remember

and tell me, the day you’re hanged, |

|

|

How you affected such a gullet’s-gripe! |

20 |

| But you,

sir, it concerns you that your knaves |

|

| Pick up a

manner nor discredit you: |

|

|

Zooks, are we pilchards, that they sweep the streets |

|

|

And count fair prize what comes into their net? |

|

| He’s

Judas to a tittle, that man is! |

|

| Just such

a face! Why, sir, you make amends. |

|

| Lord, I’m

not angry! Bid your hangdogs go |

|

|

| Drink out

this quarter-florin to the health |

|

|

| Of the munificent

House that harbours me |

|

|

| (And many

more beside, lads! more beside!) |

30 |

|

| And all’s

come square again. I’d like his face — |

|

|

| His, elbowing

on his comrade in the door |

|

|

|

With the pike and lantern, — for the slave that holds |

|

Possible self-portrait of Fra Lippo Lippi with his son Filippino Lippi

Possible self-portrait of Fra Lippo Lippi with his son Filippino Lippi

(detail from his fresco of the funeral of the Virgin Mary) |

| John Baptist’s

head a-dangle by the hair |

|

| With one

hand (“Look you, now,” as who should say) |

|

|

And his weapon in the other, yet unwiped! |

|

| It’s

not your chance to have a bit of chalk, |

|

| A

wood-coal or the like? or you should see! |

|

| Yes, I’m

the painter, since you style me so. |

|

| What, Brother

Lippo’s doings, up and down, |

40 |

| You know

them and they take you? like enough! |

|

| I saw the

proper twinkle in your eye — |

|

| ’Tell

you, I liked your looks at very first. |

|

| Let’s

sit and set things straight now, hip to haunch. |

|

| Here’s

spring come, and the nights one makes up bands |

|

| To roam the

town and sing out carnival, |

|

| And I’ve

been three weeks shut up within my mew, |

|

| A-painting

for the great man, saints and saints |

|

|

And saints again. I could not paint all night — |

|

|

| Ouf! I leaned

out of window for fresh air. |

50 |

|

| There

came a hurry of feet and little feet, |

|

|

|

A sweep of lute-strings, laughs, and whifts of song, — |

|

|

| Flower

o’ the broom, |

|

|

| Take

away love, and our earth is a tomb! |

|

|

| Flower

o’ the quince, |

|

|

| I let

Lisa go, and what good in life since? |

|

|

| Flower

o’ the thyme — and so on. Round they went. |

|

|

| Scarce had

they turned the corner when a titter |

|

|

| Like the

skipping of rabbits by moonlight, — three slim shapes, |

|

|

| And a face

that looked up . . . zooks, sir, flesh and blood, |

60 |

|

|

That’s all I’m made of! Into shreds it went, |

|

|

|

Curtain and counterpane and coverlet, |

|

|

| All the bed-furniture

— a dozen knots, |

|

|

| There was

a ladder! Down I let myself, |

|

|

| Hands and

feet, scrambling somehow, and so dropped, |

|

|

| And after

them. I came up with the fun |

|

|

| Hard by Saint

Laurence, hail fellow, well met, — |

|

|

| Flower

o’ the rose, |

|

|

| If I’ve

been merry, what matter who knows? |

|

|

| And so as

I was stealing back again |

70 |

|

| To get to

bed and have a bit of sleep |

|

|

| Ere I rise

up tomorrow and go work |

|

|

|

On Jerome knocking at his poor old breast |

|

|

| With his

great round stone to subdue the flesh, |

|

|

| You snap

me of the sudden. Ah, I see! |

|

|

|

Though your eye twinkles still, you shake your head — |

|

|

| Mine’s

shaved — a monk, you say — the sting’s

in that! |

|

|

| If Master

Cosimo announced himself, |

|

|

|

Mum’s the word naturally; but a monk! |

|

|

| Come, what

am I a beast for? tell us, now! |

80 |

|

| I was a baby

when my mother died |

|

|

| And father

died and left me in the street. |

|

|

| I starved

there, God knows how, a year or two |

|

|

| On fig-skins,

melon-parings, rinds and shucks, |

|

|

|

Refuse and rubbish. One fine frosty day, |

|

|

| My stomach

being empty as your hat, |

|

|

| The wind

doubled me up and down I went. |

|

|

| Old Aunt

Lapaccia trussed me with one hand, |

|

|

| (Its fellow

was a stinger as I knew) |

|

|

| And so along

the wall, over the bridge, |

90 |

|

| By the straight

cut to the convent. Six words there, |

|

|

|

While I stood munching my first bread that month: |

|

|

|

“So, boy, you’re minded,” quoth the good fat father |

|

|

| Wiping his

own mouth, ’twas refection-time, — |

|

|

|

“To quit this very miserable world? |

|

|

| Will you

renounce” . . . “the mouthful of bread?” thought I; |

|

|

| By no means!

Brief, they made a monk of me; |

|

|

| I did renounce

the world, its pride and greed, |

|

|

| Palace, farm,

villa, shop and banking-house, |

|

|

| Trash, such

as these poor devils of Medici |

100 |

|

| Have given

their hearts to — all at eight years old. |

|

|

| Well, sir,

I found in time, you may be sure, |

|

|

| ’Twas

not for nothing — the good bellyful, |

|

|

| The

warm serge and the rope that goes all round, |

|

|

| And day-long

blessed idleness beside! |

|

|

| “Let’s

see what the urchin’s fit for” — that came next. |

|

|

| Not overmuch

their way, I must confess. |

|

|

| Such

a to-do! They tried me with their books: |

|

|

| Lord, they’d

have taught me Latin in pure waste! |

|

|

| Flower

o’ the clove, |

110 |

|

| All the

Latin I construe is, “amo” I love! |

|

|

| But, mind

you, when a boy starves in the streets |

|

|

| Eight years

together, as my fortune was, |

|

|

| Watching

folk’s faces to know who will fling |

|

|

| The bit of

half-stripped grape-bunch he desires, |

|

|

| And who will

curse or kick him for his pains, — |

|

|

Which gentleman

processional and fine,

|

|

|

| Holding a

candle to the Sacrament, |

|

|

| Will wink

and let him lift a plate and catch |

|

|

| The droppings

of the wax to sell again, |

120 |

|

| Or holla

for the Eight and have him whipped, — |

|

|

| How say I?

— nay, which dog bites, which lets drop |

|

|

| His bone

from the heap of offal in the street, — |

|

|

| Why, soul

and sense of him grow sharp alike, |

|

|

| He learns

the look of things, and none the less |

|

|

| For admonition

from the hunger-pinch. |

|

|

| I had a store

of such remarks, be sure, |

|

|

| Which,

after I found leisure, turned to use. |

|

|

| I drew men’s

faces on my copy-books, |

|

|

|

Scrawled them within the antiphonary’s marge, |

130 |

|

|

Joined legs and arms to the long music-notes, |

|

|

| Found eyes

and nose and chin for A’s and B’s, |

|

|

| And made

a string of pictures of the world |

|

|

| Betwixt the

ins and outs of verb and noun, |

|

|

|

On the wall, the bench, the door. The monks looked black.

|

|

|

| “Nay,”

quoth the Prior, “turn him out, d’ye say? |

|

|

| In

no wise. Lose a crow and catch a lark. |

|

|

| What if at

last we get our man of parts, |

|

|

| We Carmelites,

like those Camaldolese |

|

|

| And Preaching

Friars, to do our church up fine |

140 |

|

| And put the

front on it that ought to be!” |

|

|

| And hereupon

he bade me daub away. |

|

|

|

Thank you! my head being crammed, the walls a blank, |

|

|

| Never was

such prompt disemburdening. |

|

|

|

First, every sort of monk, the black and white,

|

|

|

| I drew them,

fat and lean: then, folk at church, |

|

|

| From good

old gossips waiting to confess |

|

|

|

Their cribs of barrel-droppings, candle-ends, — |

|

|

| To the breathless

fellow at the altar-foot, |

|

|

| Fresh from

his murder, safe and sitting there |

150 |

|

| With the

little children round him in a row |

|

|

| Of admiration,

half for his beard and half |

|

|

|

For that white anger of his victim’s son |

|

|

| Shaking a

fist at him with one fierce arm, |

|

|

| Signing himself

with the other because of Christ |

|

|

| (Whose sad

face on the cross sees only this |

|

|

| After the

passion of a thousand years) |

|

|

| Till some

poor girl, her apron o’er her head, |

|

|

| (Which the

intense eyes looked through) came at eve |

|

|

| On tiptoe,

said a word, dropped in a loaf, |

160 |

|

|

Her pair of earrings and a bunch of flowers |

|

|

| (The brute

took growling), prayed, and so was gone. |

|

|

| I painted

all, then cried “’Tis ask and have; |

|

|

| Choose, for

more’s ready!” — laid the ladder flat, |

|

|

| And showed

my covered bit of cloister-wall. |

|

|

| The monks

closed in a circle and praised loud |

|

|

| Till checked,

taught what to see and not to see, |

|

|

|

Being simple bodies, — “That’s the very man! |

|

|

| Look at the

boy who stoops to pat the dog! |

|

|

| That woman’s

like the Prior’s niece who comes |

170 |

|

| To care about

his asthma: it’s the life!” |

|

|

| But there

my triumph’s straw-fire flared and funked; |

|

|

| Their betters

took their turn to see and say: |

|

|

| The Prior

and the learned pulled a face |

|

|

| And stopped

all that in no time. “How? what’s here? |

|

|

| Quite from

the mark of painting, bless us all! |

|

|

| Faces, arms,

legs and bodies like the true |

|

|

| As much as

pea and pea! it’s devil’s-game! |

|

Two paintings of Saints by Giotto di Bondone. |

| Your business

is not to catch men with show, |

|

| With homage

to the perishable clay, |

180 |

| But lift

them over it, ignore it all, |

|

| Make them

forget there’s such a thing as flesh. |

|

| Your business

is to paint the souls of men — |

|

| Man’s

soul, and it’s a fire, smoke . . . no, it’s not . . . |

|

| It’s

vapour done up like a new-born babe — |

|

| (In that

shape when you die it leaves your mouth) |

|

| It’s

. . . well, what matters talking, it’s the soul! |

|

|

Give us no more of body than shows soul! |

|

| Here’s

Giotto, with his Saint a-praising God, |

|

| That sets

us praising, — why not stop with him? |

190 |

| Why put all

thoughts of praise out of our head |

|

| With wonder

at lines, colours, and what not? |

|

| Paint the

soul, never mind the legs and arms! |

|

| Rub all out,

try at it a second time. |

|

| Oh, that

white smallish female with the breasts, |

|

|

| She’s

just my niece . . . Herodias, I would say, —

|

|

|

|

Who went and danced and got men’s heads cut off! |

|

Herod’s Banquet by Fra Lippo Lippi |

| Have it all

out!” Now, is this sense, I ask? |

|

| A fine way

to paint soul, by painting body |

|

| So ill, the

eye can’t stop there, must go further |

200 |

| And can’t

fare worse! Thus, yellow does for white |

|

| When what

you put for yellow’s simply black, |

|

| And any sort

of meaning looks intense |

|

| When all

beside itself means and looks naught. |

|

| Why can’t

a painter lift each foot in turn, |

|

| Left foot

and right foot, go a double step, |

|

| Make his

flesh liker and his soul more like, |

|

| Both

in their order? Take the prettiest face, |

|

| The Prior’s

niece . . . patron-saint — is it so pretty |

|

| You can’t

discover if it means hope, fear, |

210 |

|

| Sorrow or

joy? won’t beauty go with these? |

|

|

| Suppose I’ve

made her eyes all right and blue, |

|

Detail from Herod’s Banquet by Fra Lippo Lippi showing

Herodias

Detail from Herod’s Banquet by Fra Lippo Lippi showing

Herodias |

| Can’t

I take breath and try to add life’s flash, |

|

| And

then add soul and heighten them threefold? |

|

| Or say there’s

beauty with no soul at all — |

|

| (I never

saw it — put the case the same —) |

|

| If you get

simple beauty and naught else, |

|

| You get about

the best thing God invents: |

|

| That’s

somewhat: and you’ll find the soul you have missed, |

|

|

Within yourself, when you return him thanks. |

220 |

| “Rub

all out!” Well, well, there’s my life, in short, |

|

| And so the

thing has gone on ever since. |

|

| I’m

grown a man no doubt, I’ve broken bounds: |

|

| You should

not take a fellow eight years old |

|

| And make

him swear to never kiss the girls. |

|

| I’m

my own master, paint now as I please — |

|

| Having a

friend, you see, in the Corner-house! |

|

| Lord, it’s

fast holding by the rings in front — |

|

| Those great

rings serve more purposes than just |

|

| To plant

a flag in, or tie up a horse! |

230 |

| And yet the

old schooling sticks, the old grave eyes |

|

|

| Are peeping

o’er my shoulder as I work, |

|

|

| The heads

shake still — “It’s art’s decline, my son! |

|

The

Coronation of the Virgin

by Angelico (Giovanni di Fiesole)

|

| You’re

not of the true painters, great and old; |

|

| Brother

Angelico’s the man, you’ll find; |

|

| Brother

Lorenzo stands his single peer: |

|

| Fag

on at flesh, you’ll never make the third!” |

|

| Flower

o’ the pine, |

|

| You keep

your mistr- manners, and I’ll stick to mine! |

|

| I’m

not the third, then: bless us, they must know! |

240 |

| Don’t

you think they’re the likeliest to know, |

|

| They with

their Latin? So, I swallow my rage, |

|

| Clench my

teeth, suck my lips in tight, and paint |

|

| To

please them — sometimes do and sometimes don’t; |

|

| For, doing

most, there’s pretty sure to come |

|

| A turn, some

warm eve finds me at my saints — |

|

| A

laugh, a cry, the business of the world — |

|

| (Flower

o’ the peach, |

|

| Death

for us all, and his own life for each!) |

|

| And my whole

soul revolves, the cup runs over, |

250 |

|

| The world

and life’s too big to pass for a dream, |

|

|

| And I do

these wild things in sheer despite, |

|

The Coronation of the Virgin and Adoring Saints

The Coronation of the Virgin and Adoring Saints

by Fra Lorenzo (also called Lorenzo Monaco, meaning Lawrence the Monk) |

| And play

the fooleries you catch me at, |

|

| In pure rage!

The old mill-horse, out at grass |

|

| After hard

years, throws up his stiff heels so, |

|

| Although

the miller does not preach to him |

|

| The only

good of grass is to make chaff. |

|

| What would

men have? Do they like grass or no — |

|

| May they

or mayn’t they? all I want’s the thing |

|

| Settled for

ever one way. As it is, |

260 |

| You tell

too many lies and hurt yourself: |

|

| You don’t

like what you only like too much, |

|

| You do like

what, if given at your word, |

|

| You find

abundantly detestable. |

|

|

For me, I think I speak as I was taught; |

|

| I always

see the garden and God there |

|

|

| A-making

man’s wife: and, my lesson learned, |

|

|

| The value

and significance of flesh, |

|

|

| I can’t

unlearn ten minutes afterwards. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| You

understand me: I’m a beast, I know. |

270 |

|

|

But see, now — why, I see as certainly |

|

Saint Peter Distributing Alms

by Masaccio (Tommaso Guidi)

Saint Peter Distributing Alms

by Masaccio (Tommaso Guidi) |

| As that the

morning-star’s about to shine, |

|

| What will

hap some day. We’ve a youngster here |

|

| Come to our

convent, studies what I do, |

|

| Slouches

and stares and lets no atom drop: |

|

| His name

is Guidi — he’ll not mind the monks —

|

|

| They call

him Hulking Tom, he lets them talk — |

|

| He picks

my practice up — he’ll paint apace, |

|

| I hope so

— though I never live so long, |

|

| I know what’s

sure to follow. You be judge! |

280 |

| You speak

no Latin more than I, belike; |

|

| However,

you’re my man, you’ve seen the world |

|

| — The

beauty and the wonder and the power, |

|

| The shapes

of things, their colours, lights and shades, |

|

| Changes,

surprises, — and God made it all! |

|

| — For

what? Do you feel thankful, ay or no, |

|

|

For this fair town’s face, yonder river’s line, |

|

| The mountain

round it and the sky above, |

|

|

| Much more

the figures of man, woman, child, |

|

|

| These are

the frame to? What’s it all about? |

290 |

|

| To be passed

over, despised? or dwelt upon, |

|

|

| Wondered

at? oh, this last of course! — you say. |

|

|

| But why not

do as well as say, — paint these |

|

|

| Just as they

are, careless what comes of it? |

|

|

| God’s

works — paint anyone, and count it crime |

|

|

| To let a

truth slip. Don’t object, “His works |

|

|

| Are here

already; nature is complete: |

|

|

| Suppose you

reproduce her” — (which you can’t) |

|

|

|

“There’s no advantage! you must beat her, then.” |

|

|

| For, don’t

you mark? we’re made so that we love |

300 |

|

| First when

we see them painted, things we have passed |

|

|

|

Perhaps a hundred times nor cared to see; |

|

|

| And so they

are better, painted — better to us, |

|

|

| Which is

the same thing. Art was given for that; |

|

|

| God uses

us to help each other so, |

|

|

| Lending

our minds out. Have you noticed, now, |

|

|

| Your cullion’s

hanging face? A bit of chalk, |

|

|

| And trust

me but you should, though! How much more, |

|

|

| If I drew

higher things with the same truth! |

|

|

| That were

to take the Prior’s pulpit-place, |

310 |

|

| Interpret

God to all of you! Oh, oh, |

|

|

| It makes

me mad to see what men shall do |

|

|

| And we in

our graves! This world’s no blot for us, |

|

|

| Nor blank;

it means intensely, and means good: |

|

|

| To find its

meaning is my meat and drink. |

|

|

| “Ay,

but you don’t so instigate to prayer!” |

|

|

| Strikes in

the Prior: “when your meaning’s plain |

|

|

| It does not

say to folk — remember matins, |

|

|

| Or, mind

you fast next Friday!” Why, for this |

|

|

| What need

of art at all? A skull and bones, |

320 |

|

| Two bits

of stick nailed crosswise, or, what’s best, |

|

|

| A bell to

chime the hour with, does as well. |

|

|

| I painted

a Saint Laurence six months since |

|

|

| At Prato,

splashed the fresco in fine style: |

|

|

|

“How looks my painting, now the scaffold’s down?” |

|

|

| I ask a brother: “Hugely,”

he returns — |

|

|

| “Already

not one phiz of your three slaves |

|

|

|

Who turn the Deacon off his toasted side, |

|

|

| But’s

scratched and prodded to our heart’s content, |

|

|

| The pious

people have so eased their own |

330 |

|

| With coming

to say prayers there in a rage: |

|

|

| We get on

fast to see the bricks beneath. |

|

|

| Expect another

job this time next year, |

|

|

| For pity

and religion grow i’ the crowd — |

|

|

| Your painting

serves its purpose!” Hang the fools! |

|

Madonna

in the Forest

by Fra Lippo Lippi |

| |

|

| — That

is — you’ll not mistake an idle word |

|

| Spoke in

a huff by a poor monk, God wot, |

|

| Tasting the

air this spicy night which turns |

|

| The unaccustomed

head like Chianti wine! |

|

| Oh, the church

knows! don’t misreport me, now! |

340 |

| It’s

natural a poor monk out of bounds |

|

| Should have

his apt word to excuse himself: |

|

| And

hearken how I plot to make amends. |

|

| I have bethought

me: I shall paint a piece |

|

| . . . There’s

for you! Give me six months, then go, see |

|

| Something

in Sant’ Ambrogio’s! Bless the nuns!

|

|

| They want

a cast o’ my office. I shall paint |

|

| God in their

midst, Madonna and her babe, |

|

| Ringed by

a bowery flowery angel-brood, |

|

| Lilies and

vestments and white faces, sweet |

350 |

| As puff on

puff of grated orris-root |

|

| When

ladies crowd to Church at midsummer. |

|

| And

then i’ the front, of course a saint or two — |

|

|

| Saint

John, because he saves the Florentines, |

|

|

| Saint Ambrose,

who puts down in black and white |

|

|

| The convent’s

friends and gives them a long day, |

|

|

| And

Job, I must have him there past mistake, |

|

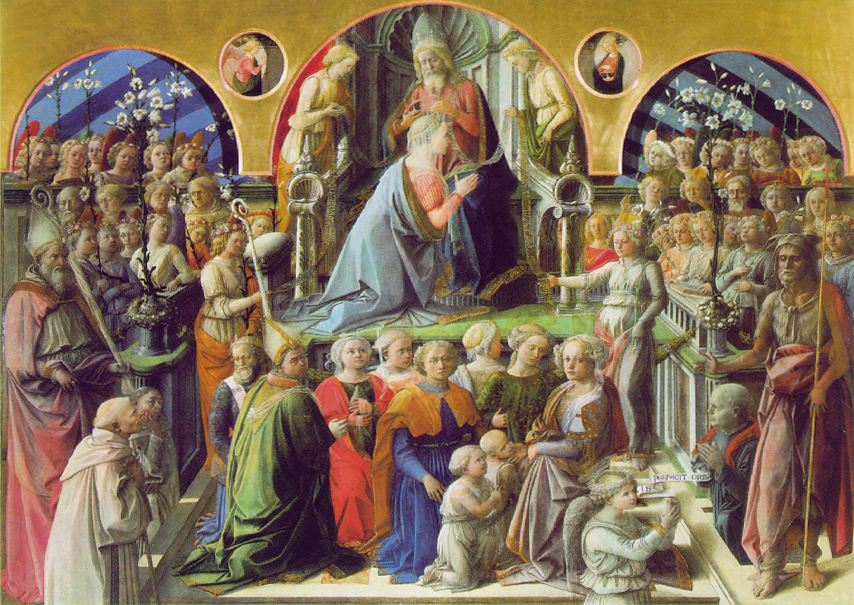

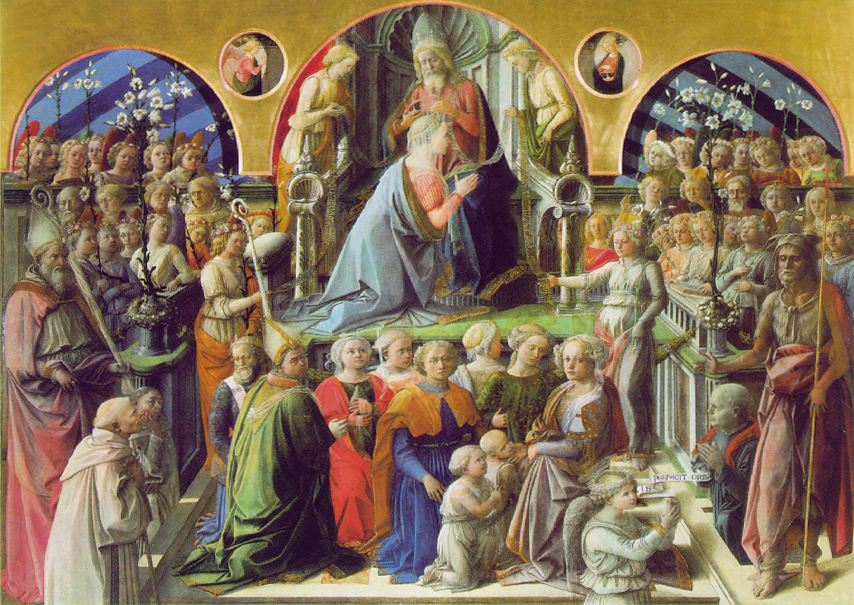

The Coronation of the Virgin

by Fra Lippo Lippi

|

| The man of

Uz (and Us without the z, |

|

| Painters

who need his patience). Well, all these |

|

|

Secured at their devotion, up shall come |

360 |

| Out of a

corner when you least expect, |

|

| As one by

a dark stair into a great light, |

|

| Music and

talking, who but Lippo! I! — |

|

| Mazed, motionless

and moonstruck — I’m the man! |

|

| Back I shrink

— what is this I see and hear? |

|

| I, caught

up with my monk’s-things by mistake, |

|

| My old serge

gown and rope that goes all round, |

|

| I, in this

presence, this pure company! |

|

| Where’s

a hole, where’s a corner for escape? |

|

| Then steps

a sweet angelic slip of a thing |

370 |

| Forward,

puts out a soft palm — “Not so fast!” |

|

| — Addresses

the celestial presence, “nay — |

|

| He made you

and devised you, after all, |

|

| Though he’s

none of you! Could Saint John there draw — |

|

| His camel-hair

make up a painting-brush? |

|

| We come to

brother Lippo for all that, |

|

|

| Iste

perfecit opus!” So, all smile — |

|

|

| I shuffle

sideways with my blushing face |

|

|

| Under the

cover of a hundred wings |

|

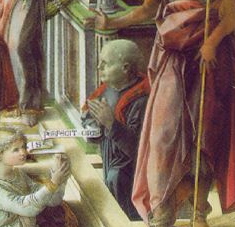

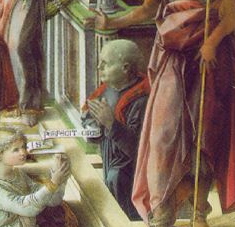

Detail from The Coronation of the Virgin

by Fra Lippo Lippi

|

| Thrown like

a spread of kirtles when you’re gay |

380 |

| And play

hot cockles, all the doors being shut, |

|

| Till, wholly

unexpected, in there pops |

|

| The hothead

husband! Thus I scuttle off |

|

| To some safe

bench behind, not letting go |

|

| The palm

of her, the little lily thing |

|

| That spoke

the good word for me in the nick, |

|

| Like the

Prior’s niece . . . Saint Lucy, I would say. |

|

| And so all’s

saved for me, and for the church |

|

| A pretty

picture gained. Go, six months hence! |

|

|

Your hand, sir, and good-bye: no lights, no lights! |

390 |

| The street’s

hushed, and I know my own way back, |

|

|

Don’t fear me! There’s the grey

beginning. Zooks! |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|