Dark Beginnings

Potsdam

The storm that broke over Berlin in June 1948 began gathering shortly after Germany's surrender in May 1945. During a meeting of the three Allied leaders at Potsdam outside Berlin in July 1945 decisions were made affecting the geopolitcal reconfiguration of Europe. Aside from formulating policies for de-Nazification and war reparations this 'Potsdam Conference' also addressed the division of Germany and Austria as well as those nations' capital cities. Unlike the more collegial environment that existed during the Allies' earlier meeting in February at Yalta the atmosphere at Potsdam was thick with tension. President Franklin Roosevelt who had a long, mutally respectful relationship with Joseph Stalin was replaced after his death by Harry S Truman, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, a casualty of spring time national elections, was replaced by Clement Attlee. The introduction of the two new unknown leaders made the naturally suspicous Soviet leader more distrustful of American and British intentions. When Truman revealed the successful nuclear weapons test at Alamogordo, New Mexico to Stalin the Premier began to fear that America would use the atomic bomb to secure global dominance. The momentum of distrust generated from that conference would carry through the first critical years of the Cold War.

Marshall Plan

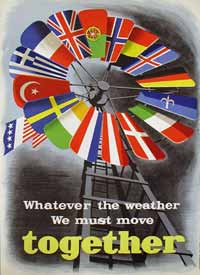

Dozens of posters were created for use as propaganda to celebrate the unity of the West and to proclaim the success of the plan. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 5 June 1947 Secretary of State George Marshall gave the commencement address at Harvard University. During his presentation he told the crowd about a new intiative to ease the suffering in war ravaged Europe. It would consist of a plan sponsored by the United States to offer billions of dollars in non-military aid to rejuvenate those ruined economies. Included in the package were food, fuel, agricultural machinery, and credits for purchase of desperately needed materials. The European Recovery Plan (ERP)was extended to nations in both the Eastern and Western occupied zones. Marshall made America's intentions clear, "It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability, and no assured peace."1

The Soviets were immediately suspicious of America's intentions and so pressured those nations under its control not to accept the offer. A wary Stalin saw in this "Marshall Plan" only the seeds of discord and duplicity and so offered his own lesser version, the 'Molotov Plan', to the countries of eastern Europe. Within one year the results of the West's efforts at economic revitalization were obvious as many nations such as Britian, France, and western Germany were benefitting from America's economic assistance. Those that did not accept the offer of help continued to wallow in depression. This caused the Soviets to lose credibility as nations in the eastern zone questioned Soviet intentions. Tensions between the East and West increased.

Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia

By February 1948 the relationship between the East and West continued to unravel. Shortly after the implementation of the Marshall Plan communist elements in the Czech National Assembly began pressuring other members to solidify a stronger relationship with the Soviets. Feeling emboldened by Soviet promises of support the Czech communists allied themselves with socialists in the government to stage a coup and grab power. On the heels of this action Czechoslovakia became part of the Eastern Bloc and the Soviets consolidated their control of Eastern Europe. Fear of a spreading Soviet hegemony alarmed the West.

Josip Broz Tito, leader of post-war Yugoslavia, balked at Stalin's efforts to exert influence over his government. Although grateful for Soviet military assistance in ousting the Nazis, Tito refused to bend to their will. As a result, Stalin ejected the Yugoslav leaders from the Communist Party, cut off aid to Yugoslavia, and enforced economic boycott by the member nations of the Eastern Bloc. Chagrined the party boss commented, "I will shake my little finger, and there will be no more Tito."2 Undaunted, Tito ever his own master, chose to remain true to socialist ideals, but led his nation on an independent path to the future with new trading partners that included the United States.

Summer Heat in Berlin

These incidents heightened tensions between the East and West still further. Taken together with the Soviets' reputation for brutal repression and voracious demands of reparations from Germany a gulf of mistrust and suspicion continued to widen between the two sides. Every action was weighed against a reaction. Finally by the summer of 1948 tensions came to a head in Berlin a city which had overwhelmingly voted against communist governance in the fall 1946 elections and which stood as a beacon of Western influence in the heart of Soviet controlled Germany.