The George Mason University campus can be considered

the epitome of the vast variety of people and cultures that are

attracted to come to the U.S. because of the allure of opportunity and

acceptance. However, upon arrival, realistically speaking, the dream is

nothing but a dream. Immigration laws, racial tensions, war. What one

may keep faith in, however, are the advancements that humankind is

possible of making. Despite how seemingly impossible it may look,

improvement is evident by looking at the progression of the past

century. The Filipino migration history is a prime example. Ranking as

one of the top 10 countries that send workers to foreign countries for

employment, the Philippines and the U.S. have had an interconnected

past in the last century. They provided a majority of the labor at

times for rigorous jobs across the country yet they faced racism and

manmade barricades that were intended to put an end to their presence

in America. However, they proved they could prevail and make their

efforts acknowledged.

Lisa O’Connor, a stay at home mother of four

that represents a diverse array of nationalities, is able to send her

children to get an education through an advantageous public school

system and enjoy her hobby of fossil hunting all because of her

father’s migration to America from the Philippines in the midst

of World War II. At the young age of 12 he and his family were a part

of the lucky wave of immigrants that left the war zone on a naval ship.

From 1920 to 1950, the O’Connors and many others arrived in the

U.S. in a populated wave of Filipinos avoiding death and poor economic

opportunity. An eagerness to work, study, and succeed still did not

prevent a plethora of obstacles from making the path to citizenship and

acceptance a long, winding road.

Seeking oversea jobs has been a prevalent part of

the Filipino culture in the past several decades. The Filipinos were

able to supply a hefty majority of laborers in the agricultural fields

of America during the 20th century. The first documented wave of

immigrants from the Philippines came in 1906 and landed in Hawaii. They

were mainly single men who were skilled to work in fields such as

agriculture.

Map of the Philippines

Map of the Philippines

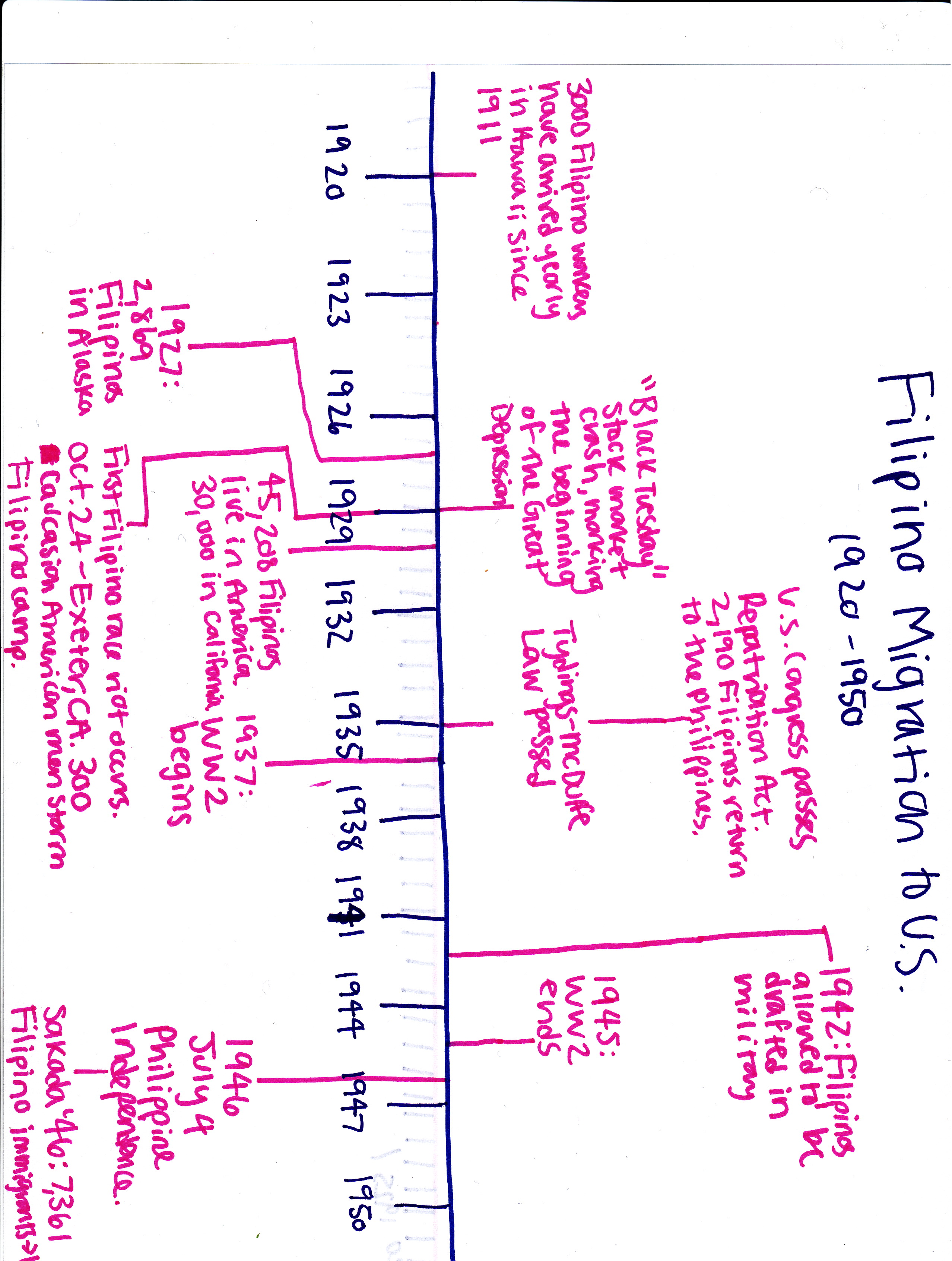

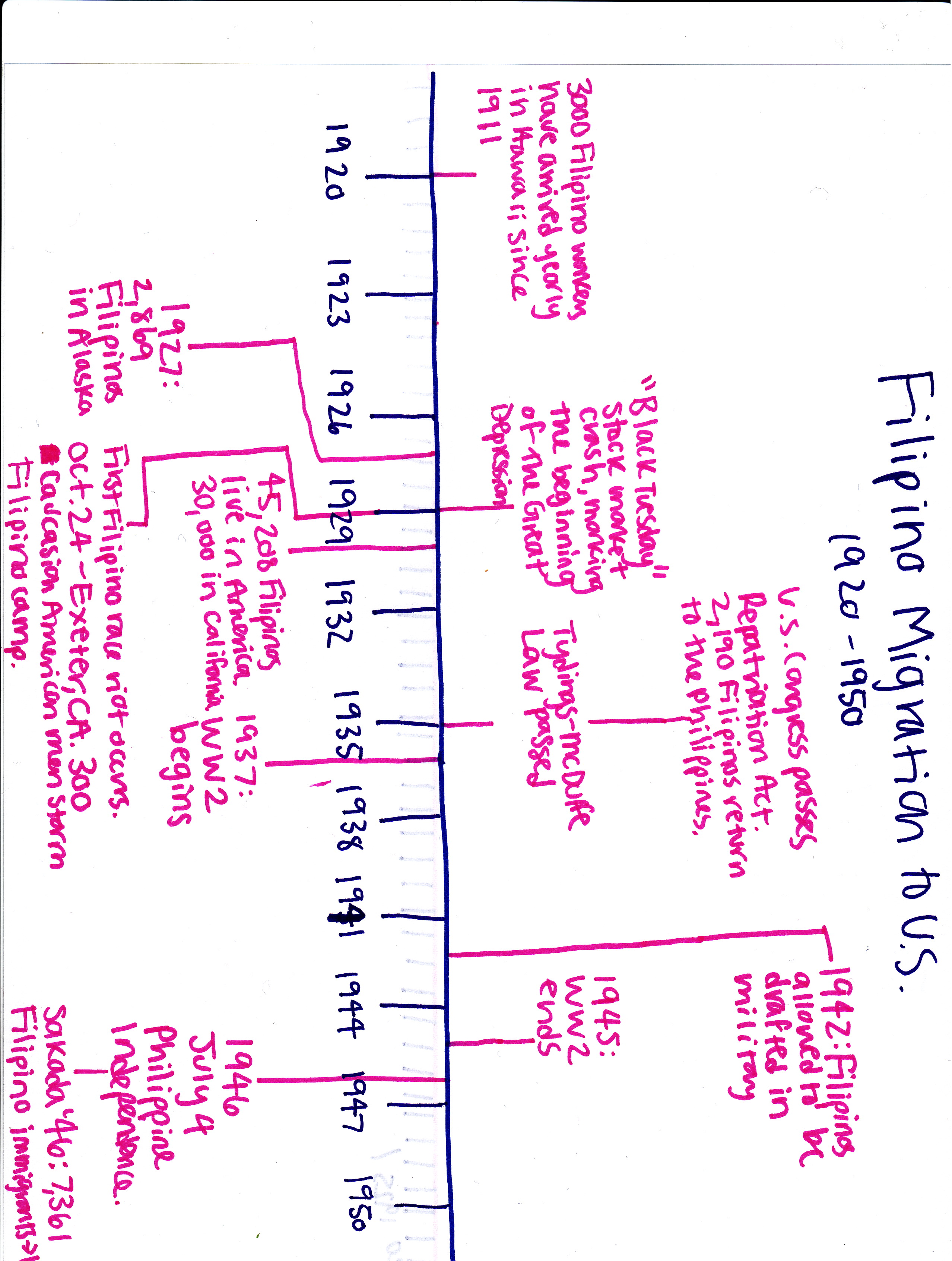

From 1911 to 1920 nearly 3000 Filipino workers arrived annually

in Hawaii (Castles 106). Anti-foreigner sentiments in the air made it a

difficult settlement for most families. America attempted to minimize

the allotted number of immigrants allowed into the U.S. by creating the

1924 Immigration Act. This act defined Filipinos as neither aliens nor

U.S. citizens, forcing them to work rigorous weeks in a country without

any benefits or acknowledgment. However employment prospects were not

hard to find at the time. The 1924 Immigration Act strictly prohibited

the Japanese from immigrating to the U.S. Due to this law, many

Japanese workers began to strike. The steep and sudden decrease in the

availability of Japanese labor worried the west coast agricultural

field. The Filipinos were very favorable for employment because they

were paid the least out of all the ethnic groups that worked in

agricultural fields at that time. Filipinos were employed in the states

of Hawaii and California as well as in the salmon cannery factories in

the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. This created tension in the U.S. as

people of other races faced fewer job opportunities.

An outbreak of racial riots began in 1929 on October 24th in Exeter,

California. “I was shocked. At the time, I didn’t feel I

was objectionable,” said Victor Merina, describing his childhood

during a period so plagued by racial tension (Asian American

Experiences in the United States, 46). On January 11th, 1930 the most

damaging riot took place in Watsonville, California.

The predominately Caucasian town of Watsonville was struggling with

major anti-Filipino sentiment for some time. The Northern Monterey

Chamber of Commerce helped create anti-Filipino resolutions. The riot

occurred when a group of Filipinos rented out a dance hall in Palm

Beach. Citizens were outraged by the fact that Filipino men would be

dancing with white women. A group of 500 Watsonville Americans raided

the dance club, beating the Filipinos viciously. One man died in the

raid. The Filipino headquarters were destroyed. Rioters attempted to

justify their actions by making such claims as the Filipinos were

undercutting wages (Migration Information).

Filipino presence caused so much controversy because they were taking

jobs from Americans. In addition, “The Filipino presence was

blamed for the decline of wages of fig, lettuce, and asparagus

harvesters” (Philippine History Site). Throughout California, the

contempt held by Americans for the Filipino’s presence ripped the

state apart. Laborers and lobbyists worked together to create a

resolution to ban Filipino immigration, just as the 1924 Immigration

Act restricted Japanese and Chinese migration. In 1929 California

called for congressional action. Coinciding with the start of the Great

Depression, the Repatriation Act was enacted in 1935. It was only

successful to an extent however, since most Filipinos chose to stay in

California. Only 2,190 Filipinos actually returned to the Philippines.

The Great Depression marked the height of Filipino exclusion in

America. During a time of intense racial terrorism and threatening

economical turmoil, Filipinos had an especially difficult time. Many

Filipinos were laid off in order to create jobs for Caucasian

Americans. In 1929 when the Great Depression began with the

“Black Tuesday” stock market crash, immigration from the

Philippines saw a significant decline. In 1934 the Tydings-McDuffe law,

also known as the Philippines Independence Act, set up the constitution

for a ten-year plan in which the Philippines gained freedom from the

U.S. The act renamed all Filipino-American residents as aliens and they

were no longer considered legally able to work in America.

The U.S. also instated 50 Filipino immigrants per year to fulfill a

quota. It was a long awaited move by much of the country. Several bills

had been presented to Congress to prevent Filipino presence in the U.S.

since the early 1920s. However both the Welch bill in 1928 and the

Shortridge bill in 1930 failed to pass, in turn failing to stop

Filipino immigration. It seemed that the only way to exclude Filipinos

would be to make the Philippines an independent nation. With the help

of Manuel L. Quezon, the leader of the Nationalist Party in the

Philippines, the act was revised to make the transition to independence

a peaceful one. These efforts were effective in ridding U.S. control of

naval bases in the Philippines, but life was still a struggle for

Filipinos living in America. The amount of impediments obstructing

Filipino’s quality of life in America continued to grow, which is

why so many Filipino immigrants would go back to the Philippines once

they had saved enough money.

In 1937 World War II began. This was a time of change for the entire

country. As the homeland had become a war zone, the U.S. once again

experienced an influx of Filipinos escaping the destruction and death

caused by massively disparaging weapons. Filipinos were banned from

joining the army until 1942 when Franklin D. Roosevelt declared them

able to be drafted. Many joined and fought in America and Asia and also

supported the U.S. in mobilization efforts.

Despite the brutality they faced while living in the country, Filipinos

saw an opportunity to put effort into bringing an end to a savage war.

Their dedication and support was not overlooked by surprised Americans

that were formerly so disgusted by their presence. The country as a

whole experienced a massive shift in attitude as the war continued. In

1940, a more clear-sighted America enacted the Nationality Act, which

allowed any noncitizens that served in the military to gain

citizenship.

In 1945 World War II ended, prompting the 1946 July 4th Philippine

Independence. After this momentous act was passed, 7361 Filipinos came

to Hawaii upon request for exemption from immigration laws in order to

keep plantations in working order. This is the last documented, massive

wave of immigration from the Philippines (Migration Information).

Without the presence of the Filipinos in America an entire century of

history would be drastically different. They shaped the country,

providing the base of labor for years in the agricultural department.

Their dedication to stay and prevail in America is so admirable as they

faced such severe obstructions of civil rights with growing racial

tensions. Their passive aggressive behavior was a sign of dignity as

they never stooped down to the level of destroying American land.

Without their presence, America would not have become the country it is

today. Lisa O’Connor and her family are living proof of how their

efforts paid off in order for their relatives to live peacefully and

happily in the states. Their caliber under such circumstances continues

to be respected and admired throughout history.

Bibliography

1. H. Brett Melendy. “Filipinos in the United States”

The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 43, No. 4. (Nov., 1974), pp. 520-547.

2. Jean Lee, Joann Faung. Asian American Experiences in the United States. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company , 1991.

3. Burma, John H. . "The Background of the Current Situation of Filipino-Americans." Social Forces 10-1951: pp. 42-48.

4. Bulosan, Carlos. America is in the Heart: A Personal History. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1941.

5. Villamin, Vicente. Filipinos in America." Washington Post 07-05-1932: pp. 6.

6. M.B. Asis, Maruja. "The Philippines' Culture of Migration." Migration Information Source Jan 2006. Accessed Feb 01 2008.

.

7. Table- http://opmanong.ssc.hawaii.edu/filipino/wwii.html