Was the “Open Door Policy” of 1900 - 1910 Beneficial to China?

U.S. Interests Come First, then Worry about Europe and China Last

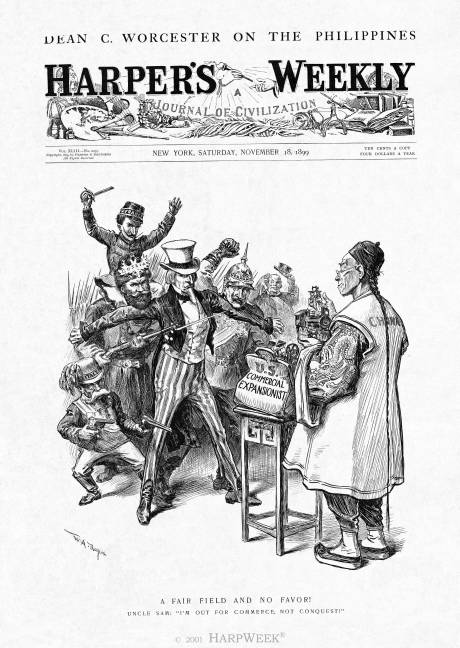

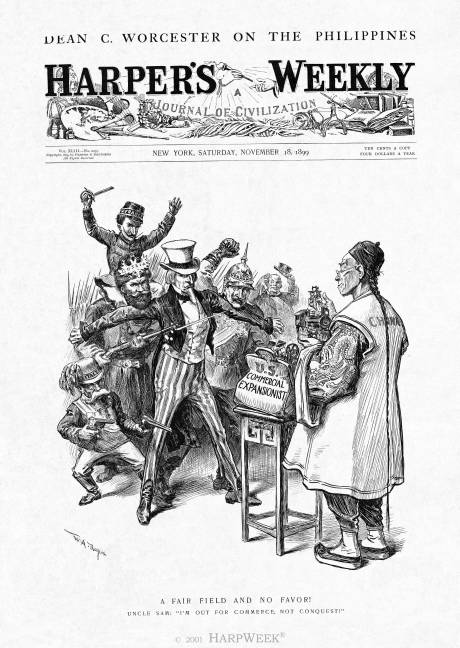

Rogers, Williams. A Fair Field and No Favor. Political Cartoon. 18 Nov 1899. HarpWeek: Cartoon of the Day.

<http://www.harpweek.com/Images/SourceImages/CartoonOfTheDay/November/111899m.jpg>.

The “open door policy” as a concept may

sound like a good idea for a supporter of a global economy, however

when it was first enforced by the United States in terms of China, the

policy was gilded (McCormick). This is because the purpose of the

policy in itself was primarily out of benefiting U.S. interest. If one

were to recall the background history leading up to the imposing of the

open door policy, the U.S. had just acquired the Philippines after the

Spanish-American War, planting them 400 miles away from China, and one

step closer to gaining access to their market (Boxer). Because there

were already existing spheres of influence in China - primarily

belonging to Britain and Japan as a result of the Sino-Japanese War and

previous imperialism, the United States also wanted to have its own

sphere of influence in China (Tignor 314). The U.S., specifically John

Hay - author of the open door notes and “open door policy”

- decided a diplomatic agreement would be best rather than using force

against China not out of concern for them, but simply because it would

not be agreeable with the U.S. citizens after having just ended a war

with the Spanish previously (Boxer).