Most people organize their lives by the day of the week - laundry on Sunday, kid's piano lessons on Thursday afternoon, but we also use a different system of months and dates which is entirely unrelated to the week. Quick, that meeting on the 15th of next month, does it conflict with driving to the piano lesson? It is so hard to go from one system to another in our head that we have to carry around a special conversion chart, called a "calendar".

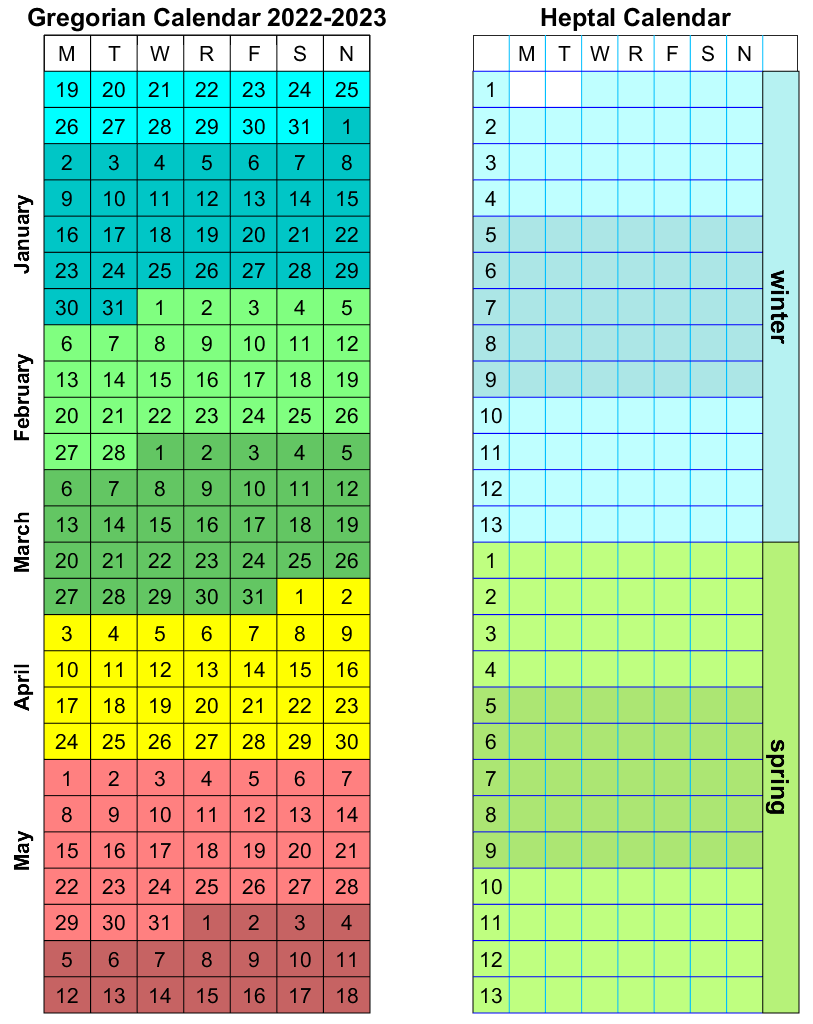

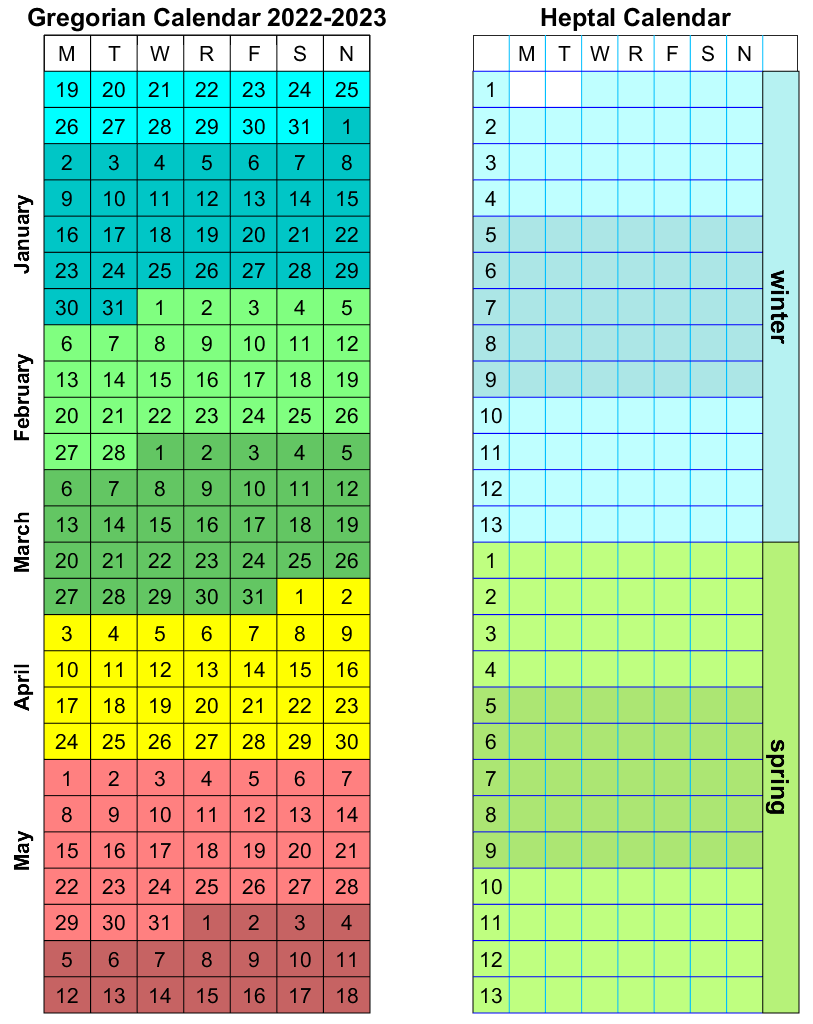

Locating an event on a specific day amounts to finding that day in the calendar's grids (see figure). The pentomino-like shape of the months (left calendar) immediately displays the randomness of the "normal" (Gregorian) calendar. Months can begin on any day of the week, with no discernable pattern. To find your way through the dates, you count up the numbers of all the days till you reach 30, 31, 28, or 29 (depending on the month and year) and then go back to 1 and start all over. Nobody would navigate on a map like that, but this is what we must traverse when we use the Gregorian Calendar to find our way in time. There is a better way

The Heptal Calendar takes its name from the Greek word for "seven" because it is based on weeks rather than months. The day of the year is completely defined by the season, week number, and day. In the calendar (right side of figure), it's row for week and column for day. That's all. An example of a date in this system is "Thursday, week 5, winter" abbreviated to "Thu 5 win" or "R5w". Months and day-of-month are not needed.

Since the week number stays unchanged for the entire week, it's easier to remember that the current week is 6 (for example) than that today is the 23rd of the month (or was it the 24th?). Setting the date for a future event using the Heptal calendar automatically tells us how many weeks between now and the event, and on which day of the week the event will occur.

Week One of winter is the week in which the winter solstice occurs. The week after Week 13 is Week 1 of spring, and similarly for Week 1 of summer and fall. Since

(4 seasons) x (13 weeks) x (7 days) = 364 days,

and a year has about 365.25 days, the starting weekday of the season drifts from year to year. For instance, if Winter starts on a Tuesday one year, in the next year it will start on Wednesday (or on Thursday in a leap year). Most of the time you don't have to think about that, just as most of the time you don't need to remember what day of the week January 1 fell on. See the FAQ's for a few other details of the system.

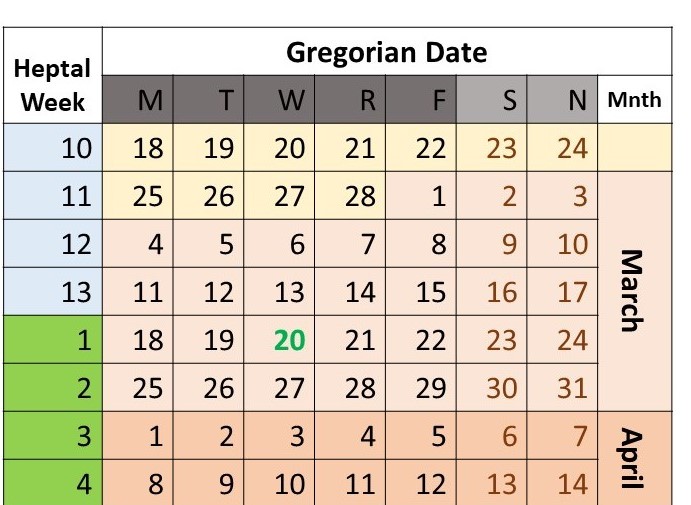

One can convert between the Gregorian system and the Heptal with a printed calendar (or app) that includes an additional column to label the number of each week (see figure). A separate page shows Heptal weeks on a Gregorian 2025 calendar. Should the Heptal calendar ever come into general use--as it should--the season/week/day system will describe dates without any need to reference months.

Good organization promotes good thinking. If the calendar is trivial to navigate, it is much easier to picture your schedule and to concentrate on other things than scrolling through the dates. "Proposal is due Tuesday week 8, this is Monday week 6, so we have about two weeks to finish." That's easier than "Today is Monday, I can't remember if it's the 24th or 25th of October, project is due Nov 8, let's see, how many days are in October? And which date is election day?"

The Gregorian calendar is based on arbitrary divisions inherited from the Roman Empire. Its months no longer serve their original purpose, to keep track of the phases of the moon. The Heptal calendar is based on the seasons, a natural rhythm experienced by all people on Earth, and weeks, our ubiquitous social division of time.

The Gregorian calendar is difficult and ugly. The Heptal calendar is convenient and elegant.

Last modified: Sun 1 win, 2026